CURZON, INDIA AND EMPIRE:

The Papers of Lord Curzon (1859-1925) from the Oriental and India Office Collections at the British Library, London

Part 1: Demi-official correspondence, c.1898-1905

George Nathaniel Curzon (1859-1925) is without question the most well known viceroy of India (1898-1905). It is also not unreasonable to claim him as the most influential, or at any rate as one among a very few British administrators in India who left an enduring mark upon that land. Curzon’s immediate predecessors, Lords Dufferin (1884-88), Lansdowne (1888-94) and Elgin (1894-98), were, in the words of one historian, ‘imperial handymen’ all. They kept the machinery of government ticking over, but accomplished little and possessed no vision for the future of India, or of the Raj. Curzon was different.

Young, energetic, Curzon, by the time he came to the viceroyalty, had already toured throughout Asia. Arriving in India at the height of the enthusiasm for empire, Curzon joined an array of imperial pronconsuls, among them Lord Cromer in Egypt, Lord Milner in South Africa, Lord Lugard in West Africa, all of whom in those years at the turn of the twentieth century were engaged in the consolidation of Britain’s empire throughout the world. All were convinced that efficient administration by autocratic but benevolent rulers best served not only Britain’s interests but those of colonized peoples.

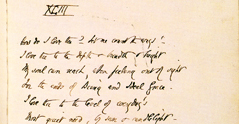

Curzon himself summarized the ideal that sustained the empire in a speech in Bombay in 1905. It was ‘to fight for the right, to abhor the imperfect, the unjust or the mean, to swerve neither to the right hand nor to the left, to care nothing for flattery or applause or odium or abuse… but to remember that the Almighty has placed your hand on the greatest of his ploughs… to drive the blade a little forward in your time, and to feel that somewhere among those millions you have left a little justice or happiness or prosperity, a sense of manliness or moral dignity, a spring of patriotism, a dawn of intellectual enlightenment, or a stirring of duty, where it did not before exist.’

From the date of his arrival in India, Curzon set on foot a thorough-going overhaul of the administrative machinery of the Raj. The Indian government, as Curzon saw it had taken on the characteristics of an elephant – regal in its gait but lumbering and slow. Among other administrative reforms, he set up a separate provincial government for the Northwest Frontier, and reorganized the sprawling provinces of the Gangetic plain to form the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh. He established a separate department of commerce and industry, and set the Archeological Survey of India on an enduring footing. Curzon cared deeply about India’s ancient monuments. For him they testified at once to India’s ancient greatness and to Britain’s role as their ‘guardian’. Curzon cherished especially the Taj Mahal, which he visited annually during his viceroyalty, and whose upkeep he supervised with a single-minded devotion to detail. Determined to make the Taj embody his idealized vision of the ‘Orient’, he even stopped in Cairo on his return to England to procure a properly ‘Saracenic’ lamp to hang above the tomb chamber.

Curzon’s last two acts of administrative reform – the Universities Act of 1904, and 1905 partition of the unwieldy province of Bengal – marked out the limits of an autocratic paternalism. The first, together with the simultaneous reorganization of the Calcutta Municipal Corporation, antagonized India’s growing educated classes by tightening government control over relatively autonomous governing bodies controlled by Indians. The second, by creating separate Hindu-majority and Muslim-majority provinces in eastern India, precipitated a massive popular protest movement that energized a dormant Indian nationalism.

Motivated in part by a desire to play Hindu against Muslim, this act was reversed, and Bengal reconstituted afresh, in 1912. Curzon’s governing strategy took no account of such bodies as the Indian National Congress, whose claims he disdained as unworthy and self-interested. Rather he sought to place India’s princes at the heart of an imperial order that took visible shape in the grand durbar of 1902. Celebrating King Edward VII’s assumption of the title of Emperor of India, this durbar brought together all of Britain’s ‘Asiatic feudatories’, but kept them confined in subordination to the ‘paramount’ power that was Britain.

Curzon resigned the viceroyalty in 1905, in a bitter dispute over army reform with the commander-in-chief Lord Kitchener. Unlike most viceroys, whose retirement brought their active political role to an end, Curzon remained a powerful figure in British life. When Asquith’s Liberal government was reconstituted under David Lloyd-George during the First World War, Curzon in 1915 joined the powerful Imperial War Cabinet. In 1919 he became foreign secretary during the delicate negotiations that marked the postwar settlement, with its dismemberment of the Ottoman, Hapsburg, and Russian empires. He continued in office until 1924, and died the following year.

The Curzon papers included in this microfilm collection thus offer the reader an unrivalled introduction to the working of the British Empire. Especially revealing is Curzon’s correspondence as viceroy with the Indian secretary in London, and with the provincial governors in India.

These private letters offer much that is not found in the official correspondence carried out through the exchange of dispatches between the India Office and the Governor-General-in-Council. Above all, as private letters between individuals, they include personal remarks, expressions of anger and annoyance directed toward other officials, comments on legislative proposals, assessment of the larger political scene, and the like. Because they range so widely, and are illuminated by the probing intelligence of a masterful viceroy, the papers collected here are an invaluable resource for students alike of Indian and of Imperial history.

Professor Thomas R Metcalf

Consultant Editor

Department of History

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

|