Consultant Editor: Harold Love, Emeritus Professor in the School of Literary, Visual and Performance Studies, Monash University.

Please see digital guide for Professor Harold Love's Editorial Introduction.

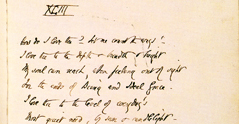

There has been great scholarly and popular interest in the witty, malicious and ingenious satires of late 17th century England ever since the appearance of Poems on Affairs of State (1702-07) and its eponymous 20th century successor from Yale University Press (1963-75).

Both of these printed collections represented the tip of an iceberg. They contain only a fraction of the political verse that circulated extensively in manuscript in the period 1660-1702, and they only touched upon the much broader volume of satirical verse which explored the concerns of Town, State and Country in the post-Restoration period.

Harold Love, in English Clandestine Satire, 1660-1702 (OUP, 2004), identified a corpus of 81 key manuscript verse anthologies from 27 libraries around the world as the primary sources with which to investigate this phenomenon of early modern popular culture. Furthermore, he made the promise that “An edition on microfilm of a large selection of these sources is planned from Adam Matthew Publications, to which the present index will be a finding list.”1

This project is the realisation of that promise. We offer the vast majority of the texts that he analysed and provided a first line index to, including manuscripts from:

• Badminton House

• The British Library

• Edinburgh University Library

• The Houghton Library, Harvard

• The Huntington Library

• The Brotherton Library, University of Leeds

• Lincolnshire Archives

• National Library of Ireland

• National Library of Scotland

• University of Nottingham, Portland Collection

• The Bodleian Library, Oxford

• All Souls College, Oxford

• Princeton University Library

• Staffordshire Record Office

• Kungelike Biblioteket, Sweden

• Folger Shakespeare Library

• Victoria and Albert Museum

• Beinecke Library, Yale

As such, this project makes available a vast body of verse from a wide variety of locations, enabling scholars to fully investigate the popular culture of the time. As Tom Cogswell has said, this verse was “as close to a mass media as Early Stuart England ever achieved.”2

In addition to allowing us to understand the political controversies of the age, the poems are also a rich source for exploring moral and sexual attitudes and also the emergence of metropolitan and urban culture, replete with its own gallery of stereotypes.

Harold Love identifies three major verse types:

• The Court Lampoon

• The Town Lampoon

• State Satire

The Court Lampoon is the best known of the three types and each is aimed squarely at a well-known individual at Court, ranging from Clarendon, Buckingham and the King, to maids of honour and court functionaries. These were generally written for a court readership, but they go beyond the level of in-jokes, raising concerns over status, political lobbying, corruption, factionalism, and impropriety. For instance:

“Have you not heard how our Soveraigne of late

Did first make a whore then a Dutches Create.”

(Yale MS Osborn fb 140, p173)

The Town Lampoon is aimed at a new range of iconic figures from the ever growing towns and cities – mayors and aldermen, sergeants and rat-catchers – and at the new modes of behaviour that were being introduced. As Love says: “A Town Satire speaks to a new social formation which was still in the process of fashioning its identity. Satire was a means of asserting this community’s independence …, or training its members in acceptable modes of deportment, and of articulating shared values.”3 The verse had a powerful normative role and is useful today to see the changes that were taking place in society. For example, there is much on the rise of the professional classes as well as on the practice of ‘visiting’ that was part of the new sociability.

State Satire has a broader canvas and attacks more general examples of corruption and incompetence. Religion is often a target, as are major issues of national political significance such as the Dutch Wars. In an age before the widespread existence of newsprint, this genre helped to spread information across the country, albeit with a fair degree of spin, and played an important role in establishing public opinion. One such verse is aimed at Lord Chief Justice Scoggs and his summary justice in response to the Popish Plot:

“Within this House lives justice Scroggs

Who hath killed more men, than his Father did Hogs.”

(Yale MS Osborn b54, p1103)

The second and third types of satire extend way beyond London and reach into clubs, associations, universities and gossip shops across Britain. There are examples of verses written while visiting the baths at Tunbridge Wells, or at balls and dinners – all of which help to extend the value of this genre to the study of social history.

Many of the verses are anonymous, which is not surprising given their vitriolic content. A great number were also written in answer to earlier verses, as a form of literary combat, conjuring the image of the ‘Renegado Poet’. Those who did reveal their identity risked physical danger, either in the form of a beating (as Dryden found out, following an exchange with Rochester) or death following a duel.

Much work has been done to identify the authors and we now know that these include: Ayloffe, Baber, Behn, Dorset, Dryden, Eland, Etherege, Faulkland, Heveningham, Howe, Martin, Marvell, Mordaunt, Prior, Pulteney, Rochester, Sedley, Shadwell, Sheppard, Vaughan, Villiers, Walsh and Wharton. And there were many women writers, as was remarked upon at the time:

“Female Lampooners a new fashion’d thing.

Lord! Unto what excess will Women bring

This Age?”

(Manchester, Chetham’s Library MS Mun A.4.14, p91)

In addition to writing many satires, Aphra Behn helped to compile Bod MS Firth c16. Katharine Sedley, former mistress of James II, wrote many sharp pieces and was described as:

“A wither’d Countess… who rails aloud,

At the most reigning vices of the Croud.”

(Leeds, Brotherton Library MS Lt 38, p207)

Sarah Cowper, great-grandmother of the poet, was also a fan of such verse and compiled ‘Poems Collected at Several Times from the year 1670’ (Herts. R.O. D/EP F/36 & F/37).

There are many notable volumes within the collection. Yale MS Osborn fb 140, for instance, is the only known manuscript source for satires of the early 1660s. Entitled ‘A Collection of Poems, Sayters and Lampoons’ it starts with pre-Restoration drollery poems and anti-Puritan satires, then proceeds to a 1670 state satire – ‘The King’s Vows’ – then earlier court satires such as ‘On the Duke’s Servants’ and ‘The Court Ladies.’

These sources will provide countless opportunities for research. Quite apart from the detailed exploration of the political and popular culture of the period and the study of the poetry produced, it will also be possible to study the process of manuscript transmission and to compare numerous variant texts of a single item. Equally it will be possible to study numerous texts focussing on a single issue. The jostling of ideas and insults will bring the period alive, as Selden suggested in his Table Talk:

“More solid things doe not shew the Complexion of the Times so well as Ballads and libells.”

1 Harold Love, English Clandestine Satire, 1660-1702 (OUP, 2004), p303.

2 Thomas Cogswell, writing in Amussen & Kishlansky (edd) Political Culture and Cultural Politics in Early Modern England (Manchester University Press, 1995).

3 Harold Love, English Clandestine Satire, 1660-1702 (OUP, 2004), pp67-68.