FOREIGN OFFICE FILES: UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Series Two: Vietnam, 1959-1975

(Public Record Office Classes FO 371 and FCO 15: South East Asia Department)

Part 6: Vietnam, 1967-1968

(PRO Class FCO 15/481-782)

Part 6 focuses on the continued build up of American forces in Vietnam and the growing number of peace initiatives to try to resolve the conflict. Weekly reports, intelligence assessments and critical analyses bring together news from Saigon, Hanoi, Haiphong and Dien Bien Phu, offering a British and Commonwealth perspective on US policy, the motives and debates influencing decision making, the scale of the human tragedy, the efforts at mediation and peace talks to end hostilities.

The Vietnam War had wide-reaching implications; it was destined not to confine itself to Vietnamese borders, with the interlocking geographical and political nature of the region ensuring that more nations would become immersed in the increasingly complex conflict. Whilst Britain was not directly involved in Vietnam she had substantial interests throughout South-East Asia and was anxious to monitor the situation closely. The Foreign Office files included in this collection reflect this and the growing concerns of the Wilson Government, documenting the events which led to an intensification of the conflict and the involvement of far greater numbers of American combat troops.

Part 6 focuses on 1967-1968 including:

- the impact of US bombing of North Vietnam.

- the exchange of letters between President Johnson and Ho Chi Minh.

- the continued build up of American forces in Vietnam.

- the Tet offensive.

- the capture of Hué.

- the partial bombing halt, de-escalation and changes in American policy.

- the Paris peace talks.

The British and Commonwealth viewpoint offers scholars different perspectives and insights on the formulation of US policy and strategy, the day to day situation on the ground, the refugee crisis, the impact of the conflict on the whole region, and its bearing on east-west tensions and international politics.

The files offer up lots of material to look at questions such as:

- What were the weaknesses of Johnson’s concept of a “limited conflict” to stop communist “aggression”?

- How isolated did President Johnson become?

- What were the main reasons for the escalation of the conflict?

- What was the response to the huge refugee crisis?

- How significant was the impact in America of domestic public opinion?

- How damaging was American intervention for the political and social infrastructure of South Vietnam?

- What role did China and the Soviet Union play in terms of indirect support, military aid and diplomatic intervention?

- Who was winning the propaganda war?

- Why were various peace initiatives frustrated?

- What progress was made at the Paris peace talks?

The following extracts give a flavour of the material.

At the start of 1967 the US administration was divided over strategy; President Johnson had been escalating the war steadily for eighteen months, with little impact. The air campaign of the previous year had destroyed hundreds of bridges, but virtually all of them had been rebuilt or quickly bypassed. Against a background of the intensified US bombing of North Vietnam, the British Government renewed its diplomatic initiatives to try to find a way to end the war.

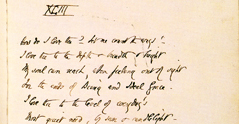

Revised draft statement by the Prime Minister in response to escalation of

US bombing of targets in North Vietnam, 18 June 1966

“We are convinced that the United States forces are taking, as always, every precaution to avoid civilian casualties. Nevertheless, we have made it clear on many occasions that we could not support an extension of the bombing to the areas of Hanoi and Haiphong. Our concern throughout the Viet Nam conflict has been over the twin dangers that the war will spread, and that suffering and distress are placed upon innocent people. We believe that the value of each application of military strength must be judged not only in terms of military needs but also in terms of the risk of injury to those not directly involved in the conflict.

For these reasons, when President Johnson informed me that it might become necessary to attack targets in or on the outskirts of the populated areas of Hanoi or Haiphong, while he assured me that these attacks would be directed specifically to the oil installations, I notified him that Her Majesty’s Government must formally dissociate themselves from such action.

Nevertheless, Her Majesty’s Government believe that the United States is right to continue helping the millions of South Vietnamese who have no wish to live under Communist domination, until such time as the North Vietnamese Government abandon their attempt to gain control of South Viet Nam by force and accept the proposals for unconditional negotiations repeatedly put forward by the United States as well as by Britain and the Commonwealth. Her Majesty’s Government are convinced that the North Vietnamese refusal alone prevents these negotiations and deplore Hanoi’s constant rejection of the path of peace… ” (See FCO 15/590)

Parliamentary Labour Party: Discussions on Vietnam

Draft Statement for the Secretary of State’s use at the PLP meeting on

2 February 1967

This draft begins: “We have discussed Vietnam many times before and many of you will know very well what I have to say. Nevertheless, if there is still any doubt about the Government’s attitude to the war and our efforts to get it stopped, then I am glad to set out once again, as clearly as I can, where the Government stands….

The overriding aim of our policy is to get the war stopped and to promote a settlement which will allow the people of Vietnam - and indeed all South East Asia—to develop in peace, in their own way and without any outside interference.

I suggested a way in which this might be done in the Plan I put forward at Brighton on 6 October last year and again at the United Nations General Assembly in New York on 11 October. However, I recognise that, although this seems to me to be the best way forward, it is not the only way and we are ready to support and promote other proposals if they should seem to offer any chance of achieving peace.

But meanwhile, day by day new reports come in about incidents in this wretched war. Some of you have said that the Government should dissociate themselves from, and condemn American policy and American use of modern weapons. But the sufferings of this war are not confined to North Vietnam alone nor are they caused only by the Americans.

I detest, as I am sure we all do, the bombing and the use of such weapons as napalm. But I detest also the Vietcong terrorist mine, which kills indiscriminately both soldiers and civilians, both adults and children. I detest the weapons of assassination and terror. I detest all war and if I were to condemn, I would want to condemn not one side or the other, but all those who bring suffering to the Vietnamese people.

I respect the honestly-held feelings about the distress and suffering caused in North Vietnam. But I ask those who hold these views to be careful lest their honesty is put to ignoble account by the Communists. I believe that a carefully planned campaign has been launched by Hanoi to present their case in the whitest possible way.

This is getting us into a moral imbalance which is just as dangerous as a military or political imbalance. As I said at Brighton, this would nurture the seeds of a new conflict. We need a balanced settlement—with balanced de-escalation and a balanced cease fire as part of it...”

(See FCO 15/615)

Top Secret, UK Eyes Only Telegram No. 49 of 11 January 1967, from Mr Colvin in Hanoi, to the Foreign Office

“I learn from Canadian Permanent Representative that Commissioner is (repeat is) engaged in clandestine discussions over negotiations. Moore’s contact is with Foreign Minister and is “partly” on behalf of U Thant. Talks are not connected with Salisbury. He gave me impression that some of the initiative was coming from North Vietnamese whose conciliatory attitude had surprised him. I could learn nothing more and apologised for incomplete report…Canadians emphasised secrecy as essential to success and I must ask you to maintain United Kingdom eyes proviso if only to preserve him as my continuing source.” (See FCO 15/582)

On a visit to Guam, 20-21 March 1967, President Johnson meets with Thieu and Ky and visits injured US soldiers in hospital.

Note by P H Gore-Booth, 21 April 1967, to Sir D Allen re: Secretary of State’s Visit to Washington DC for discussions on Vietnam

“…Mr Rusk was afraid of further escalation but felt that it was very difficult to persuade the President to keep a foot on the brake if absolutely nothing was happening in the way of peace efforts. The President was only too prone to argue that Mr Rusk’s advice had been “wrong so far”. This meant that, increasingly, the President was getting advice from Walt Rostow who was in these matters a hard liner and, in Mr Brown’s judgement, not adequate to the great responsibility which fell on him… Mr Johnson himself was feeling an increasing isolation and that this, combined with what he had seen of the impact of the war, both on service people and on Senate and Congress, were making him more emotional and less objective about the situation. (He had been enormously affected by some of the cases he had seen in hospital in Guam)… ” (See FCO 15/663)

John McNaughton, an advisor to US Secretary of Defense McNamara, and a certified hard-liner in the Pentagon a year earlier, by Spring 1967 was noting sadly to McNamara that people think that “we are trying to impose some US image on distant peoples we cannot understand, and that we are carrying the thing to absurd lengths”. He feared what lay ahead, possibly “the worst split in our people in more than a century…” – some possible 21st century echoes here. The looming split over Vietnam was to be compounded by the US Government’s increasing isolation from its public. McNaughton commented wryly that McGeorge Bundy, George Ball and Bill Moyers, all of whom had at least had the guts to voice misgivings about the war, had resigned. And, McNaughton asked ominously, “Who next?” McNamara, increasingly disillusioned with the progress of the war, was to be replaced in Spring 1968.

These divisions and potential splits in the US Administrative are closely scrutinised by the British Embassy in Washington DC and by the Foreign Office officials in London. Their minutes frequently refer to an “increasingly isolated President Johnson…”

FCO 15/735 covers discussions with US Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge during his European Tour. Ellsworth Bunker took over from Henry Cabot Lodge as US Ambassador in Saigon at the start of May 1967.

FCO 15/701 looks at the concept of an electronic barrier in Vietnam, the so-called “McNamara Line”.

Towards the end of June 1967 there were talks between Soviet Prime Minister Kosygin and President Johnson in New Jersey. The British Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, believed that his Soviet counterpart could be persuaded to pressure the North Vietnamese into seeking some kind of compromise. With some misgivings President Johnson accepted the British proposal to try to get Kosygin to co-operate. Chester Cooper acted as a liaison man in London, but the British felt that several good opportunities were wasted in 1966 and in 1967.

There are lots of files on Soviet policy - see FCO 15/558, FCO 15/621, FCO 15/633-634 covering Kosygin’s visit to the UK, FCO 15/666-667 on the British Foreign Secretary’s visit to Moscow, FCO 15/668 with details on Soviet weapons and military supplies in Vietnam, FCO 15/709 on Harold Wilson’s visit to Moscow and FCO 15/732 on exchanges between the UK and the Soviet Union regarding possible peace moves. UK proposals for Three Power talks on ending hostilities are covered in FCO 15/580-582.

National Vietnam Week in 1967

It actually aroused little media interest in the UK and the expectations of Lord Brockway “for the biggest national demonstrations of his lifetime” were not fulfilled. This file includes lots of data on public opinion in the UK with briefing notes for MPs. The file includes a copy of the newspaper “Vietnam, Our Neighbour”, June 1967, published by the International Committee of Conscience on Vietnam (ICCV), with a poignant and graphic illustration on its front cover. (See FCO 15/565).

Large clusters of files such as FCO 15/598-602 focus on US policy. These are full of reports from the British Embassy in Washington DC.

Telegram from Sir Patrick Dean, Washington DC, to Foreign Office, 16 August 1967

“Following Personal for Prime Minister. Repeated for Information to Mr George Thomson, Minister of State, Foreign Office. Personal. Vietnam.

The President summoned me this afternoon and asked me to convey the following information to you. The President said that he was distressed that recent speeches and Newspaper Articles here were causing you concern and possible embarrassment. He wanted you to be informed about the present bombing policy. The US Government had recent firm information that the Soviet Government was at present powerless to bring about a negotiation or a Conference. If the Russians had the power they would probably wish to use it but they had not. The US Government also had very good information that Hanoi was not in the least interested at present in trying to reach a settlement. On the contrary, they wanted to go on. At the same time, the US Government calculated that up to 700,000 North Vietnamese were tied down in trying to repair the damage done by the US bombing. The President did not want to see these men set free to reinforce the North Vietnamese Army and the Vietcong. The President said that there were about 350 industrial targets which were of prime importance to the North Vietnamese war effort and which the US Air Force would like to attack. In practice, about six out of seven of these plants had been and would be kept under attack. The remaining 50 or so would not be attacked because they were so situated that the risks of killing substantial numbers of civilians were too great. For instance, there was no intention to bomb or to attempt to close Haiphong Harbour as such or to attack the shipping in it. The only targets on the list in or close to Hanoi were the power plants and oil installations. The Joint Chiefs of Staff would like to bomb the remaining 50 Plants, but the President was not going to agree for the reasons stated.” (see FCO 15/602, Telegram No. 2674)

Telegram from Sir Patrick Dean, Washington DC, to Foreign Office, 17 August 1967

“I asked Mr Rusk today whether he foresaw the possibility of a renewed diplomatic attempt to begin negotiations after the present phase of the bombing had come to an end. Mr Rusk said that this might be so but that a great deal depended on the reaction both inside and outside Vietnam after the forthcoming elections there. This was very difficult to foretell. He wished to make it clear moreover that hardly a week passed without the US Government testing out the reactions from Hanoi in one way or another. The public position of the Hanoi Government was on record in the correspondence between President Johnson and Ho Chi Minh...” (see FCO 15/602, Telegram No. 2689)

McNamara, testifying before a Senate sub-committee in August 1967, described “American bombing of North Vietnam as …ineffective”. By Spring the following year, Clark Clifford had succeeded McNamara. Clifford was soon embroiled in studies of troop requests. He quickly came out against the idea of a further build-up.

On 3 September 1967 in South Vietnam, Thieu, despite a very poor performance, was elected President with Ky as Vice-President. It was plain that the elections would do nothing to alter the course of the war. However, President Johnson was able to portray the newly elected regime to the American public as a legal government. In return, his South Vietnamese allies could continue to count on considerable US military and economic aid. Many observers were left dissatisfied as the South Vietnamese generals continued their internal squabbles.

Various files, such as FCO 15/622, look at NLF strategy.

The new program of the National Liberation Front

Max J T McCann (British Embassy, Phnom Penh) writing to R A Fyjis-Walker (SE Asia Department, Foreign Office), 5 September 1967

The Representative of the South Vietnam National Liberation Front in Cambodia,

M. Nguyen Van Hieu, held a press conference in Phnom Penh on 2 September dealing with a recently held Extraordinary Conference of the NLF and the promulgation of the Front’s new political programme. Most of what was said was the usual propaganda, though references to bogus proposals put forward by the Americans for peace and negotiation; to the farce of presidential and parliamentary elections in South Vietnam; and an appeal by the Congress to patriotic Vietnamese to eliminate their political differences, may give some clue to the apprehensions which inspired the calling of the Congress and the decision to issue what is called a new political programme...”

There follows a detailed summary of all the key points of the new program.

(see FCO 15/622)

President Johnson speaking in San Antonio on 29 September 1967 declared that the US would halt its bombing campaign in exchange for “productive discussions”. This gave renewed hope for a fresh wave of diplomatic initiatives.

American troop strength in Vietnam was close to half a million by the end of 1967.

31 January 1968 saw start of the Tet Offensive as nearly 70,000 Communist soldiers launched surprise attacks on more than a hundred cities and towns, including Saigon. This moved the war into a new setting - South Vietnam’s supposedly impregnable urban areas. In many places the Communists were swiftly crushed by overwhelming American and South Vietnamese military power. Viet Cong commandos attacked the US Embassy in Saigon. Some of the fiercest fighting and worst atrocities took place in Hué, which was recaptured by US forces on 25 February 1968, after a prolonged battle of twenty-six days.

In 1968 Westmoreland requested 206,000 additional American troops. Clark Clifford, succeeding McNamara as Secretary of Defense, rejected the idea of a further build-up of forces. Consequently, Westmoreland was appointed Army Chief of Staff and replaced in Vietnam by General Creighton Abrams.

On 25 March 1968, the so-called “wise men” met in Washington DC to advise the President against further escalation; on 31 March President Johnson announced a partial bombing halt, offered peace talks and declared that he would not run for re-election. North Vietnamese diplomats arrived in Paris in mid-May for talks with the American delegation headed by Averell Harriman.

The British continued to pin great hopes on Soviet pressure brought to bear on the North Vietnamese. The Foreign Office hoped such pressure might yield results in Paris.

Soviet Policy on Vietnam

Gerald Clark (British Embassy in Moscow) in his letter to R B Dorman (SE Asia Department at the Foreign Office), 24 July 1968

...In view of the pessimistic tone which now pervades the reporting here about the Paris talks, it is perhaps worth repeating that the communiqué issued at the end of the President of India’s visit on 18 July said “In the opinion of both sides (ie Soviet Union and India) the talks going on in Paris and direct contacts can lay the foundation for the cessation of war in Vietnam and for the peaceful solution of the Vietnam question...”

(see FCO 15/621)

Soviet External Policy

Analysis of Mr Gromyko’s Speech on 27 June 1968

...The decision to discuss missiles, the emphasis on the Soviet Union’s great power status and the expressed interest in taking part - by implication with the United States - in the solution of major international questions suggest that the Russians are more ready to assert publicly that on certain issues at least the concurrence of the super powers is essential and that co-operation between them is necessary...”

(see FCO 15/621)

The file draws a contrast between the style and approach of Kosygin and Brezhnev and their different speeches:

"We know well enough that the two men are very different in their approach. On the rare occasions when Mr Kosygin has tried to use Brezhnev-type language he has been transparently uncomfortable. This is not because he is indifferent to ideology or because his devotion to the Communist cause is less than complete. It is because by temperament and training he is a man who is able to look at a problem fairly objectively and who seeks a victory for his side by practical means, unclouded by dogmatic extravagance. Mr Brezhnev reacts more violently and is less intelligent...”

(Analysis by H F T Smith, Northern Department, Foreign Office, see FCO 15/621).

FCO 15/698 is one of a number of interesting and detailed files on UK policy on South Vietnam. It includes a White Paper published by the Republic of Vietnam, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Saigon 1968, on “The War in Vietnam: Liberation or Aggression?”

The same kind of issues and questions are mirrored in a discussion paper written in 1967 by Alain Enthoven, a senior assistant to McNamara, an expert on European defence issues at the Pentagon.

Stanley Karnow in Vietnam: A History (Pimlico revised and updated edition, 1994) describes Enthoven as “an inside observer, with no professional ax to grind” as he “dealt only tangentially with Vietnam”. Karnow argues that Enthoven’s perceptive analysis focussed around the key point: “The real force confronting the United States in Vietnam was less Communism than the strongest political current in the world today – nationalism. That force had welded the North Vietnamese together through more than twenty years of almost uninterrupted fighting.” It would, he argued, “inspire them to continue to endure great hardship.” Thus, the American bombing would not “hurt them so badly as to destroy their society or, more to the point, their hope of conquering all Vietnam.” The basic challenge for America was to promote an “equally strong” sense of nationalism in the South. Without that, “we will have lost everything we have invested…no matter what military success we may achieve.” He cautioned that a big US build up would ultimately weaken South Vietnam. “If we continue to add forces and to Americanize the war, we will only erode whatever incentives the South Vietnamese people may now have to help themselves in this fight. Similarly, it would be a further sign to the South Vietnamese leaders that we will carry any load, regardless of their actions.”

In many files, there is evidence that the British kept information back from the Americans - often to protect the anonymity of their sources.

D F Murray Top Secret Minute to Mr Samuel, 27 March 1968

re: Weekly Survey of Intelligence

"…The phrase “administrative and political void” is a quote from Dr Do who also referred to fear in the towns. Dr Do is purposely not identified as a source since this report is read by the Americans who may not know the extent to which Dr Do lets down his hair with us: he may be saying very different things to Mr Bunker, but to Mr Maclehose he is sober, realist and almost always gloomy. ” (See FCO 15/490)

American proposals leading to the Paris peace talks are the subject of FCO 15/736-739.

Sir Patrick Dean (Washington DC) to Sir Paul Gore-Booth (Foreign Office), in a letter headed “Vietnam”, dated 30 April 1968

“Dear Paul,

Further to my letter to the Secretary of State of 27 April, I asked Walt Rostow today whether he could give me an insight into the President’s personal thinking about Vietnam, bearing in mind that the President himself had told me with great vehemence at the Diplomatic Reception last week that he was quite determined to bring about peace if he possibly could.

Rostow said that he thought that an agreement on a site for the talks would be found. The President, however, did not think that the posture to adopt before a negotiation was “to get down on his belly”. He was convinced that Warsaw had been chosen in order to humiliate the United States and her Allies, and the President was personally very displeased with the Poles. They had proved to be unreliable intermediaries…”

(see FCO 15/738)

Finally, President Johnson stopped the US bombing campaign in North Vietnam. A whole series of files are devoted to the Paris Peace Talks. As well as FCO 15/736-739, see also FCO 15/743-746. UN debates are covered in FCO 15/687.

Foreign Office Background Note on Vietnam headed:

“Secretary of State’s talks with Mr Katzenbach”

“…To our Ambassador in Washington Mr Rusk has made it clear that the Americans have no intention of being hustled into the wrong place. Mr Rusk seems prepared for the bargaining process on a meeting place to go on for some time and to recognise that the North Vietnamese are not more likely to accept the second list of proposed places than the first; they are represented in none of the new capitals suggested and Paris, which opinion in general would expect Hanoi to accept, has been omitted by the Americans… ”

(see FCO 15/738)

Vietnam: The Paris Talks

D F Murray to Mr Wilkinson, Foreign Office note of 9 May 1968

“On the eve of the United States/North Vietnamese bilateral talks in Paris, I submit a memorandum to which I have rather euphemistically given the title of “Prospects.” [this was a 9 page document]. The purpose of this memorandum is to set out as simply as possible what I would estimate to be the objectives of both sides in these discussions, and also to highlight the major problems – all of them depressingly complex – which are likely to arise as soon as the talks get beyond the opening courtesies…” (see FCO 15/738)

There is lots of material on the propaganda of both sides. See FCO 15/756-759 for assessments of captured North Vietnamese and Viet Cong documents. FCO 15/758 includes a 60page Top Secret booklet compiled by the North Vietnamese entitled “Resolution of the Central Office for South Vietnam”.

However, the British Foreign Office prided itself in the need for balanced analysis. Plenty of information was kept back from the Americans and there was no sense in which pro-American propaganda would be seen as anything other than what it was. Information was gathered from all sources. There are numerous files which document the views of various countries – European nations such as Germany, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Yugoslavia, Italy, Switzerland, Denmark, Belgium, Norway and Sweden - the attitudes on Vietnam of Commonwealth countries such as Australia, New Zealand and Canada, as well as feedback from those closer to the field of conflict - Thailand, Pakistan and Indonesia.

The activities of Cuban military missions were carefully monitored - see FCO 15/562 and 568. The Foreign Office also took careful note of Chinese attitudes, the Sino-Soviet situation and the impact of Chinese policy on the war.

Walt Rostow’s visit to the UK is described in FCO 15/779; included are the briefing notes for the Prime Minister for discussions on Vietnam.

Relief activities, care for war orphans and refugees are also important topics – see files such as FCO 15/722-726 and FCO 15/768.

As 1968 drew to a close, many of the files contain comments on the prospects for 1969, the new American President and his team, the progress of covert negotiations as well as faltering events in Paris. Richard Nixon had been elected President of the United States on 5 November, choosing Henry Kissinger as his National Security Adviser. Kissinger, like Nixon, believed that the war had to be ended “honorably” for the sake of America’s global prestige. No sooner was he installed in the White House than Kissinger directed his staff to canvass American officials in Washington DC and in Saigon for their appraisals of the prospects for Vietnam. American troop strength in Vietnam at 31 December 1968 stood at a total of 540,000 front-line soldiers. The following year would see the start of some significant withdrawals as part of the US policy of “Vietnamization” as Kissinger sought an agreement that would give the Saigon Government a reasonable chance of survival - a “decent interval” as Kissinger later described it - allowing the Americans to complete troop withdrawals and pass full control to a viable South Vietnamese Government.

|