OLIPHANT: The Correspondence and Literary Manuscripts of Margaret Oliphant (1828-1897) from the National Library of Scotland

What is Margaret Oliphant's rightful place in the pantheon of literature? To her contemporaries she "belonged to the race of literary giants.... Mrs Oliphant has been to the England of letters what the Queen has been to our society as a whole." (Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol 162, July-December 1897, pp161-4). A review in the Daily News commented that "With the exception of George Eliot, there is no female novelist of the day comparable to Mrs Oliphant." (1 July 1869). J M Barrie said that he would "like to lead the simple man by the ear down the long procession of her books. ...there are so many fine figures in it." (writing in the Introduction to A Widow's Tale, 1898).

Yet, after her death in 1897, her reputation went into a steep decline. Perhaps it was because she was too closely identified with the Victorian Age. Perhaps it was the result of posthumous criticism by Thomas Hardy, whom she had sharply criticised when he was a young writer. Perhaps it was because, like Trollope, Oliphant wrote a great deal. Indeed they once compared their respective tallies on an occasion when Trollope dropped in for tea, and he was amazed to find that he had been outwritten. In her life she produced 98 works of fiction and 26 of non-fiction, in addition to more than 50 short stories and over 300 articles and reviews.

There is now a movement to reinstate Oliphant as a canonical author. It is fuelled by the realisation that she did write refreshingly realistic and non-sentimental novels depicting the struggles of women, the problems of marriage and the difficulties of parent-child relationships. The debate will continue as to whether she would have produced more masterpieces if she had written fewer books. But there can be no doubt that works such as The rector and The doctor's family, Salem Chapel, Mrs Marjoribanks, A Beleagured City, Kirsteen, and Diana Trelawney merit her a place in any list of great nineteenth century novelists.

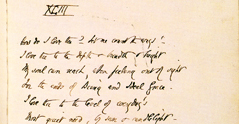

We now make it possible to undertake a thorough assessment of her life and work by making available the major collection of her surviving manuscripts. We include over 25 volumes of her correspondence, 4 volumes of her diaries, the complete text of her manuscript Reminiscences (sections of which were later published as her Autobiography), and a number of key literary manuscripts such as the holograph version of her first work - Margaret Maitland.

Among the correspondents are Thomas and Jane Welsh Carlyle, Thomas Chalmers, Sir Henry Craik, Geraldine Jewsbury, Anna, Lady Ritchie and Sir Walter Scott. More revealing than all of these, is her correspondence with John and William Blackwood, her main publishers, who supported her throughout her career. There are also many family letters.

These sources help to provide a rounded picture of Margaret Oliphant as a writer, as head of the household after the death of her husband when she was only 31, and as a mother. They portray a life punctuated with death and debt, in which her family and her writing were her only real respite.

Born near Musselburgh, Midlothian in 1828, Margaret Oliphant Wilson was the youngest of three children born to Francis and Margaret Wilson. Moving to Liverpool in 1838, she became a keen reader and on 24 August 1849 Henry Colburn, the London publisher, offered to publish Passages in the life of Margaret Maitland (1849), her first work. Her reputation grew with the publication of Caleb Field (1851) by Hurst & Blackett. Returning to Edinburgh in 1851, she gained entrance to Edinburgh literary society and her meeting with Christopher North and Major William Blackwood initiated a relationship that was to last for nearly fifty years. She became a regular contributor to Blackwood's Literary Magazine and Katie Stewart (1853) was her first serialized novel for them.

In 1852, aged 24, with 4 novels under her belt already, she married her cousin Frank Oliphant, a designer of stained glass windows who worked for Augustus Pugin, the great Gothic revivalist. The young couple honeymooned in Germany and Margaret returned expecting a baby. Life seemed to hold infinite promise. Pugin was not well though and, after a brief spell of madness, he died. Frank's business was never solvent thereafter. As was common at this time, children came rapidly with Maggie (born 1853), Marjorie (born 1854, died 1855), Cyril (born 1856) and Stephen Thomas (born & died 1857). In addition to the enduring the rigours and hazards of childbirth, and running a crowded household, Oliphant had to write to support herself, her children, her husband and his business. Fiction of this period, such as Harry Muir (1853), TheQuiet Heart (1854) and The days of my life (1857) dwell on stress and anxiety.

Despite their financial difficulties the Oliphants travelled en masse to Italy via France in 1859. The timing was not good. War broke out in Europe, France invaded Italy just as they were crossing the border and they reached Florence to find a battle-zone. They witnessed the rise of Victor Emmanuel II who took control of the city which finally became part of the new Italy in 1861. On moving to Rome in May 1859 it became clear that Frank had developed tuberculosis and he died in October, leaving Margaret, pregnant again, deserted in a foreign country with the children. She stayed with friends while she recovered and wrote to her friends to plead for financial support. Not for the last time, John Blackwood gave her funds and they enabled her to return to England after the birth of Cecco, and to relocate to Elie in Fife.

She owed £1,000 and Frank's life insurance was only worth £200. Oliphant started to do translation work and commenced work on The life of Edward Irving (1862), the preacher, but it became clear that Blackwood's were losing faith in her. At this point she returned home and sat up all night to write The Executor, a short story. Written out of desperation, this became the first of the highly successful Chronicles of Carlingford.

The rector and the doctor's family and Salem Chapel both appeared anonymously in 1863 and many attributed them to George Eliot. Thomas Carlyle, whom she had met in 1861 to interview regarding her work on Irving, declared her to be "worth whole cartloads of Mulocks, and Brontës, and THINGS of that sort" and her financial difficulties were resolved with a £1,500 advance from Blackwood's for her to write The Perpetual Curate (1864).

Never one to allow money to sit idly, Oliphant took her family on a further European tour. As well as visiting France and Switzerland, the high point was to be a visit to Rome in `happier times' so that she would not always associate the city with her husband's death. Alas, after two months in the city, her cherished eldest daughter, Maggie, fell ill and died within four days. Oliphant returned to London and set up house in Kensington in 1865. She had written Miss Marjoribanks (1866) and A son of the soil (1866) while travelling and the former, sharply humorous, is generally regarded as one of her greatest works.

Oliphant put a great deal of herself in her novels. Death and destitution are never far away and she is noteable for her portrayal of strong female characters. She is no feminist, but her novels are shot through with depictions of the alienation of women (from parents, husbands, children and the world).

Charles Dickens paid her £1,000 in 1866 for Madonna Mary (1867) which was serialized in Household Words. By now, Oliphant was a central figure in Victorian Literature, avidly read by Queen Victoria, Darwin and Gladstone among others.

Oliphant moved to Windsor and Cyril was sent to Eton. Then, in 1868 there was another crisis. Her brother Frank, a picture of stolidity and reliability with a steady job at the Bank of England, ran away to France, losing his job and imperilling his family. His wife set off after him, leaving Margaret Oliphant with bills to pay and two further children to look after. The fiction continued to flow, with Brownlows (1868), The Minister's Wife (1869) and The three brothers (1870 - written for Trollope's St Paul's magazine), and she received a Civil List Pension of £100 pa following a meeting with the Queen in 1868. But in 1870 she received further dreadful news from Europe. Frank wrote to tell her that his wife, Jeannie, was dead. Frank and his other two children returned to England and went to live with Margaret. She was now supporting a man and six children, none of them working.

Non-fiction works such as the Memoirs of Count de Montalembert (1872) and The makers of Florence (1876) gave her excuses to take her family on trips to Europe and one continues to get the impression of money being spent almost as soon as it is earned. However, her burden eased when one of Frank's sons set sail for India in 1875 (where he died four years later). Frank died later in the year.

In 1879 the Oliphant household moved to Oxford, where Cyril and Cecco were at university. Despite early promise, Cyril failed to find a job until he was 25 and both boys were a drain on their mother's resources. During this time, Oliphant met Turgenev who was being presented with an honorary degree. She commented "I don't think such a thing was ever offered either to Dickens or Thackeray. I am a mere woman, incapable of honours....” She wrote A Beleagured City (1880) which was a great success and she started to write supernatural tales.

Her efforts were then deflected to literary history as Macmillan offered her £1,000 to write a Literary History of England in the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century (1882). She was generous in her praise of other authors and paid particular attention to women authors and the rise of Gothic Fiction. She visited Venice to research The makers of Venice: Doges, conquerors and men of letters (1887) and continued to write fine fiction including The Ladies Lindores (1883) a story about two sisters who are due to be married off, which is a study in angst and mental cruelty, which was followed by its sequel Lady Car (1889). Another fine work of this period is Kirsteen (1890) in which a woman chooses a career over relationships and children.

In 1890 she visited Palestine to research Jerusalem: its history and hope (1891), but on her return Cyril, who had spent some time in Ceylon, died aged 33. In the winter of 1890 she travelled to the Swiss Alps with two of the children and read Sir Walter Scott's Journal. She discovered a deep affinity with her countryman who had also spent much of his life writing to pay off debts. Early in 1891 she collapsed with severe internal pains, but she continued to write fiction and non-fiction including The railwayman and his children (1891) and Memoirs of the life of Laurence Oliphant and Alice Oliphant his wife (1891 - Laurence Oliphant, writer, traveller and a Liberal MP during the Reform Bill Parliament had been a friend since 1867, but was not a relative).

At this time Blackwood's asked her to write their official history and she began to write it concurrently with Makers of modern Rome (1895), her Autobiography and her increasingly popular supernatural stories.

Virginia Woolf commented that "Mrs Oliphant sold her brain, her very admirable brain, prostituted her culture and enslaved her intellectual liberty in order that she might earn her living and educate her children...." (writing in Three Guineas). Having devoted herself to her children, it was a tragedy that Cecco, her sole surviving child, contracted tuberculosis and died in 1894.

Margaret Oliphant moved yet again, this time to Wimbledon and continued to write four works a year. Aged 69, she travelled to Siena to research a book on that city, but her attacks of pain resumed with a vengeance and she returned to England to be told (to her relief) that they were a sign of her approaching death.

At 11.35pm on the evening of Friday 25 June 1897, in the midst of the Queen's Jubilee celebrations, Margaret Oliphant Wilson Oliphant died. Symbolic of her life, the proofs of Annal of a publishing house: William Blackwood and his sons, their Magazine and friends (1897) were at her side - she had worked to the end.

Her Autobiography was published in 1899, edited by Mrs H Coghill.

There are many reasons why the writings of Margaret Oliphant should be looked at again. She is certainly one of the most important women writers of the Victorian period, and one who wrote perceptively about family issues and women's lives.

She was a giant of popular fiction, and a pioneer of supernatural fiction. Her biographical, historical, and topographical writings and literary criticism enable us to root her fiction in a broader framework of people, places and literature.

In addition to the manuscripts brought together here, we also publish the Collected Writings of Margaret Oliphant covering all of her fiction and non-fiction writing that appeared in book form. As such, scholars will be able to examine the complete range of her writing and reassess her reputation.

|