HEMANS: The Literary Manuscripts of Felicia Hemans (1793-1835)

“the Italy of human beings.”

Maria Jane Jewsbury

“The 19th century celebration of Hemans’s exemplary womanliness may be deafening, but for the critics who have helped to rehabilitate her in the last decade, Hemans represents another ideal: a subtly transgressive feminist, collapsing the gender constructions she appears to endorse and criticizing the social order which imposes such limits on women.”

Frances Wilson, writing in the London Review of Books, 16 November 2000

The poetry of Felicia Hemans was read and admired by Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Ann Evans, Walter Scott, Florence Nightingale, Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Queen Victoria. She sold more books of poetry during the Romantic era than anyone but Lord Byron and Walter Scott. Though she died in 1835, her work remained central to literary culture throughout the nineteenth century. In fact, she was embraced during the Victorian period as not only one of the great poets but as a paragon of Victorian womanhood. This despite the fact that her marriage broke down after five years and she spent most of her adult life as the breadwinner of a large family, supporting her five boys as well as her mother and sister. Her best known volume – Records of Women – contains imaginative portraits of strong women throughout history and from a variety of cultures, from abandoned brides to martyred heroines.

And yet, in the 1990s, the Romanticist Jerome McGann was compelled to ask: Do we remember any of her poems?” How then did her star fall?

Felicia Dorothea Browne was born in Liverpool on 25 September 1793 – the product of a cosmopolitan marriage between George Browne, an Irish merchant, and Felicity Dorothea (née Wagner), the daughter of an Italian diplomat. Felicia was the fifth of seven children and was a precocious child with a great memory and a gift for languages. At an early age she could speak English, Italian and French and she later learnt Latin, German, Spanish and Portuguese. She also had a musical ear and had a talent for drawing.

The convulsions in Europe caused by the French Revolution in 1789 and following caused problems for her father’s business and, as a result, the family moved to Gwrych near Abergele in Denbighshire, Wales in 1800. W M Rossetti describes the place as “close to the sea and amid mountains … the very scene for the poetically-minded child to enjoy.” She spent the next nine years there, although she visited London in 1804, aged 11 and was impressed with displays of art and sculpture. Her father departed for Quebec during this period, but he was a broken man, whose business had failed and he died abroad in 1812 – so her mother was the dominant parental figure in her life. In November 1807 a French army commanded by General Junot swept into Spain and Portugal and precipitated the Peninsular War (1807-1814), in which Britain and Spain successfully combated the French forces. Two of Felicia’s brothers served in the conflict with Sir John Moore and the 23rd Royal Welsh Fusiliers. She idolized them and later commented “that I could almost fancy I had passed that period of my life in the days of chivalry, so high and ardent were the feelings they excited.”

In 1808, when she was just 14, she published her first volume, titled simply Poems.

The publication was made possible by the financial assistance of a family friend, but it still had a healthy list of 978 subscribers including William Roscoe (who also wrote the Preface), Samuel Galton and a young Miss M Oliphant. The verse was of variable quality, although remarkable for so young a poet. It earned a harsh notice in the Monthly Review, but it did demonstrate a facility with language and a clear grasp of romantic sentiment, as is shown in her poem entitled ‘Melancholy’:

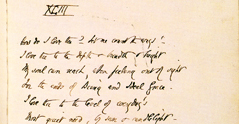

MELANCHOLY

When autumn shadows tint the waving trees,

When fading foliage flies upon the breeze;

When evening mellows all the glowing scene,

And the mild dew descends in drops of balm;

When the sweet landscape placid and serene,

Inspires the bosom with a pensive calm;

Ah ! then I love to linger in the vale,

And hear the bird of eve's romantic tale;

I love the rocky sea-beach to explore,

Where the clear wave flows murmuring to the shore;

To hear the shepherd's plaintive music sound,

While Echo answers from the woods around;

To watch the twilight spread a gentle veil

Of melting shadows o'er the grassy dale,

To view the smile of evening on the sea;

Ah ! these are pleasures ever dear to me.

To wander with the melancholy muse,

Where waving trees their pensive shade diffuse.

Then by some secret charm the soften'd mind

Soars high in contemplation unconfin'd,

To melancholy and the muse resign'd.

1808 also saw the publication of England and Spain; or, Valour and Patriotism, inspired by her brothers’ service in the Peninsular War. It was a powerful condemnation of Napoleon and a rallying call for freedom and liberty in the face of tyranny:

Too long have Tyranny and Power combin'd,

To sway, with iron sceptre, o'er mankind;

Long has Oppression worn th' imperial robe,

And rapine's sword has wasted half the globe!

It ends by calling for peace:

Bid war and anarchy forever cease,

And kindred seraphs rear the shrine of peace;

Sales were disappointing. 1809 saw a further downturn in the family’s financial position and they moved again to Bronwylfa, near St Asaph, Flintshire, in Wales. At one point the young Felicia met with Thomas Medwin, a cousin of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s, whose descriptions of her beauty and poetic talents prompted Shelley to write to her. It came to nought, as Mrs Browne decided he was unsuitable and put an end to the correspondence. At about the same time Felicia also met Captain Alfred Hemans, a friend of her brother’s on leave from the Spanish campaign. He found her bewitching and she professed her love to him, but they didn’t see each other again until 1811, when he made a formal proposal. He was not rich and was very much older than Felicia, so he was told to cool his ardour for a year. But their love did not diminish and they were married at St Asaph Cathedral on 30 July 1812. They took up residence in Daventry, Northamptonshire, where he was appointed Adjutant to the County Militia. The marriage was certainly a productive one with the birth of five boys - Arthur, George, Claude, Henry and Charles – between 1813 and 1818.

1812 witnessed Napoleon’s disastrous campaign in Russia and the publication of Hemans’s The Domestic Affections, and other poem. Both were to cause friction in the marriage. Lack of money and close family support for Felicia caused them to move back to live with her mother in St Asaph in 1813. This was probably not a comfortable situation for Captain Hemans, who also had to deal with his wife’s apparent success. The situation got worse with the end of the war in Europe in 1815, for there was no longer a need for a large standing militia; Captain Hemans was made redundant in 1817. At the same time, Felicia Hemans began to gain a reputation as a poet. She sent a poem to Walter Scott that had been inspired by reading Waverley and he had it published in the Edinburgh Annual Register. She also had successive volumes of poems published by John Murray, including The Restoration of the Works of Art to Italy (1816), Modern Greece (1817) and Translations from Camoëns and other Poets (1818, together with original verse). The first of these, on the return of Italian treasures from the Louvre to their former homes in Italy was praised by Byron who called it “a good poem – very”.

At this point the Hemans marriage (six years and five boys) was effectively over. We do not know the precise details, but Captain Hemans departed for Italy “for the sake of his health” just before the birth of his fifth son. He never returned. W M Rossetti describes the excuse as “a very inconvenient motive, or a highly convenient one according to the circumstances” and he quotes from a memoir by Harriett Hughes, Felicia’s sister:

“It has been alleged, and with perfect truth, that the literary pursuits of Mrs Hemans, and the education of her children, made it more eligible for her to remain under the maternal roof than to accompany her husband to Italy.”

Maria Jane Jewsbury also suggested that Captain Hemans was uneasy living off his wife’s income. Felicity and Felicia, mother and daughter, were certainly very close, and both helped to raise the children while Felicia’s writing career went from strength to strength, as she realized the earning potential of her skills as a writer.

In 1819 she published Tales and Historic Scenes in Verse, which incorporated earlier verse with new material and quickly went through three editions. In the same year she also won a £50 prize for her poem, Wallace's invocation to Bruce: a poem, which was published in Blackwood’s Magazine. This was followed in 1820 with The Sceptic, which she described as “a picture of the dangers resulting to public and private virtue and happiness, from the doctrines of Infidelity.” It has been interpreted variously as a philosophical exploration of perils of scepticism, an attack on Byron, and a critique of contemporary sexual politics. Byron took the attack personally and responded with fierce criticism. The whole debate raised her profile and prompted a meeting and subsequent friendship with Reginald Heber, then Rector of Hodnet, in Shropshire. He liked her religious orthodoxy and encouraged her to write another poem, Superstition and Revelation on faith.

In 1821 Hemans won another prize (50 guineas), awarded by the Royal Society of Literature for the best poem on Dartmoor. This was followed with a new collection of verse, Welsh Melodies, which included a gothic flavoured account of a night on Cader Idris:

The Rock of Cader Idris

I lay on that rock where the storms have their dwelling,

The birthplace of phantoms, the home of the cloud;

Around it for ever deep music is swelling,

The voice of the mountain-wind, solemn and loud.

'Twas a midnight of shadows all fitfully streaming,

Of wild waves and breezes, that mingled their moan;

Of dim shrouded stars, as from gulfs faintly gleaming;

And I met the dread gloom of its grandeur alone.

I lay there in silence–a spirit came o'er me;

Man's tongue hath no language to speak what I saw:

Things glorious, unearthly, pass'd floating before me,

And my heart almost fainted with rapture and awe.

I view'd the dread beings around us that hover,

Though veil'd by the mists of mortality's breath;

And I call'd upon darkness the vision to cover,

For a strife was within me of madness and death.

I saw them–the powers of the wind and the ocean,

The rush of whose pinion bears onward the storms;

Like the sweep of the white-rolling wave was their motion,

I felt their dim presence,–but knew not their forms !

I saw them–the mighty of ages departed–

The dead were around me that night on the hill:

From their eyes, as they pass'd, a cold radiance they darted,–

There was light on my soul, but my heart's blood was chill.

I saw what man looks on, and dies–but my spirit

Was strong, and triumphantly lived through that hour;

And, as from the grave, I awoke to inherit

A flame all immortal, a voice, and a power !

Day burst on that rock with the purple cloud crested,

And high Cader Idris rejoiced in the sun;–

But O ! what new glory all nature invested,

When the sense which gives soul to her beauty was won !

Her venture into drama was less successful, but tells much about the reputation and contacts that she had made. She completed The Vespers of Palermo: a tragedy, in five acts in 1823 and Charles Kemble mounted a production at Covent Garden by the end of the year. It closed after one night, but this did not discourage Joanna Baillie from prompting an 1824 Edinburgh production with Elizabeth Siddons in the main role and with an epilogue written by Sir Walter Scott.

In 1825 she moved across the River Clwyd to Rhyllon and the difference between the two houses is suggested in her poem: Dramatic Scene between Bronwylfa and Rhyllon.

Whilst Bronwylfa was a small but pleasant home, covered in roses and blending in with its surroundings, Rhyllon was a tall brick house, standing out proudly like a dragon in the beautiful valleys. Her sister describes this as the happiest period of Felicia’s life – with the boys spending much of the time outdoors.

She appeared increasingly in the periodical press. For instance, she made 171 appearances in the New Monthly Magazine between 1823 and 1835 and 75 appearances in Blackwood’s Magazine between 1826 and 1835. Then, in 1825, she published The Forest Sanctuary, a collection of poems that included ‘The Lays of the Many Lands’ series, generally regarded as one of her finest volumes of poetry. Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot) was among its many admirers, declaring it “exquisite!” The volume went through three English editions, one German edition and two American editions, commencing with a Boston edition in 1827.

This was really the beginning of her great success in America. Peter Cochran quotes an article in the North American Review for April 1827, which contends:

“The highest value is set on every effort of mind connected with the investigation of truth, or the nurturing of generous and elevated sentiments…. Where the public mind has thus been formed, the poetry of Mrs Hemans was sure to find admirers.”

Another review in the Christian Examiner praised her “glorious poems” and stated:

“Her poetry, so full of deep sentiment, so pure, and elevating, calls up images and emotions, like those with which we view the brilliancy of the evening star in the stillness of a summer night.”

The author of both was Professor Andrews Norton of Harvard Divinity School and he championed her work and even offered her the editorship of a magazine. A fourth edition of her Poems was published in New York in 1828 and over the ensuing years she became the most anthologized writer in literary annuals and gift books published in America. The writer and editor, Lydia Sigourney, another admirer, was even described as “the American Hemans.”

The death of her mother in January 1827 was a heavy blow for Felicia Hemans, causing a profound grief from which she never fully recovered. In the following year she moved from Wales back to Wavertree in Liverpool, and her two eldest boys went to Italy to live with their father.

1828 saw the publication of Records of Women, which was her last great volume of verse. It included a number of long poems that became instant favourites with her audience, including ‘Arabella Stuart’, ‘Properzia Rossi’, ‘The Peasant Girl of the Rhone’ and ‘The American Forest-Girl’. This volume also included a poem that would become one of her best-loved works, “The Homes of England.” She writes with great fluency and her verse has a sonorous quality as seen in this extract from ‘Joan of Arc’:

JOAN OF ARC, IN RHEIMS.

That was a joyous day in Rheims of old,

When peal on peal of mighty music roll'd

Forth from her throng'd cathedral; while around,

A multitude, whose billows made no sound,

Chain'd to a hush of wonder, tho' elate

With victory, listen'd at their temple's gate.

And what was done within?–within, the light

Thro' the rich gloom of pictur'd windows flowing,

Tinged with soft awfulness a stately sight,

The chivalry of France their proud heads bowing

In martial vassalage!–while midst that ring,

And shadow'd by ancestral tombs, a king

Receiv'd his birthright's crown. For this, the hymn

Swell'd out like rushing waters, and the day

With the sweet censer's misty breath grew dim,

As thro' long aisles it floated o'er th' array

Of arms and sweeping stoles. But who, alone

And unapproach'd, beside the altar-stone,

With the white banner, forth like sunshine streaming,

And the gold helm, thro' clouds of fragrance gleaming,

Silent and radiant stood?–The helm was rais'd,

And the fair face reveal'd, that upward gaz'd,

Intensely worshipping;–a still, clear face,

Youthful, but brightly solemn!–Woman's cheek

And brow were there, in deep devotion meek,

Yet glorified with inspiration's trace

On its pure paleness; while, enthron'd above,

The pictur'd Virgin, with her smile of love,

Seem'd bending o'er her votaress.–That slight form!

Was that the leader thro' the battle storm?

Had the soft light in that adoring eye,

Guided the warrior where the swords flash'd high?

In 1829, an enlarged edition of The Forest Sanctuary was published, including new lyrics such as ‘Casabianca’, which had first appeared in a periodical in 1826, but came to be memorized by thousands of school children both in England and America for the next hundred years.

Hemans was restless in Liverpool and started a series of travels to Scotland and the Lake District, where she met with Scott and Wordsworth. She got on well with Scott who declared “There are some whom we meet, and should like ever after to claim as kith and kin; and you are one of those.” Her visit also prompted a very favourable review of her work in the Edinburgh Review by Francis Jeffrey. She was delighted by the Lake District, staying two weeks at Rydal Mount near Ambleside and a further two months close to Lake Windermere. To Wordsworth she wrote:

Thine is a strain to read among the hills,

The old and full of voices;–by the source

Of some free stream, whose gladdening presence fills

The solitude with sound; for in its course

Even such is thy deep song, that seems a part

Of those high scenes, a fountain from their heart.

In 1831 she moved to Dublin to be close to her brother George. She continued to write, although she was now an invalid. Songs of the Affections (1830), National Lyrics, and songs for music (1834) and Scenes and hymns of life, with other religious poems (1834) were her last three collections of verse and were of an increasingly religious nature. Her frail state was brought to the attention of Sir Robert Peel, the Prime Minister, who sent her a cheque for £100 to ease her condition, and promised a clerkship for her youngest son.

Felicia Hemans contracted scarlet fever in 1834, which further weakened her condition, and she died in Dublin on 16 May 1835 from a respiratory infection that turned to ague, aged 41. She was buried at St Anne’s Church in Dublin. Her sons were now 17, 18, 19, 20 and 21 and all were well set in life. Both Laetitia Landon (‘L.E.L’) and Elizabeth Barrett wrote commemorative stanzas and Wordsworth subsequently described her as “that holy Spirit, sweet as the Spring” (‘Extempore effusion upon the death of James Hogg’).

Blackwood’s issued a 7-volume collected edition of her works with a memoir by her sister, Harriett Hughes, from 1839 onwards and dozens of different editions of her ‘poetical works’ were published in America between 1836 and 1867. In expansionist America and in imperialist Britain she was seen as one of the great advocates of duty and patriotism and she inspired a new generation of women writers, as well as poets such as Tennyson.

Her fame continued throughout the Victorian period and her works stayed in print until just after the First World War, with a major edition of her works appearing in 1920.

So what precipitated her decline? Was it a generational shift? Or did a nation traumatised by a world war dismiss her notion of the nobility of dying for duty’s sake? Or was it the onset of modernism and a new style of poetry against which her prominent rhyming schemes and use of poetic language (with words such as o’er, ‘twas and ‘midst) now seemed somewhat arch? All of these factors played a part – as did the fact that the public no longer had a stomach for didacticism and sentimentality.

She also suffered from her own popularity. Works such as ‘Casabianca’ were ruthlessly parodied in music halls and in the playground. The famous opening lines:

The boy stood on the burning deck

Whence all but he had fled;

The flame that lit the battle’s wreck

Shone round him oe’r the dead.

were an easy target for comic versifiers. Amongst the least bawdy versions was:

The boy stood on the burning deck,

His feet all covered in blisters,

The flames reached up and burned his pants,

And now he wears his sister's.

These comic versions were still in mass circulation in the 1930s and 1940s. Another Hemans poem that was parodied was ‘The Homes of England’, which began:

The stately Homes of England,

How beautiful they stand!

Amidst their tall ancestral trees,

O'er all the pleasant land.

In this case the parodist was Noël Coward, who wrote:

The stately homes of England,

How beautiful they stand,

To prove the upper classes

Have still the upper hand.

Perhaps Coward’s parody was inspired by the quotation that she placed at the head of the verse: “Where's the coward that would not dare / To fight for such a land?”

The rebirth of interest in Hemans’ work began in the 1980s and 1990s. Peter Trinder’s brief biography of Mrs Hemans appeared as part of the ‘Writers of Wales’ series and a group of scholars – including Norma Clarke, Paula Feldman, Gary Kelly, Anne Mellor, Julie Melnyk, Marlon Ross and Nanora Sweet – have all suggested new critical approaches to her work.

One of the most obvious problems for scholars is access to the sources. The University of Pennsylvania has provided free access to the majority of her printed output through their digital library (see the web resources that follow). However, her manuscripts are widely dispersed.

We are delighted to have been able to work with Professor Paula Feldman to bring together a good number of the outstanding sources in this project.

We offer access to the three major archives at Liverpool City Library (including her commonplace book, seventeen autograph poems, letters and other material), Trinity College, Dublin (Commonplace entries, several volumes of manuscript poems and a good number of letters) and the National Library of Wales (twenty letters, two more collections of manuscript poetry and many individual poems). To these we have added other significant sources from the Harry Ransome Center, University of Texas, Austin; Bedfordshire & Luton Archives; Trinity College, Cambridge; Derbyshire Record Office; the Representative Church Body, Dublin; the University of Liverpool Library; London Metropolitan Archive; the Society of Antiquaries Library; the Wellcome Institute; Nottinghamshire Archives; and the British Library.

We are grateful to all of these archives for their co-operation and to Professor Feldman for providing us with the list of sources to track down. This list is reproduced in the digital guide for the convenience of scholars.

Hemans is a major writer whose work deserves to be re-examined. We hope that the publication of these sources will provide fresh impetus to scholarly investigation.

Web Resources and Select Bibliography

Web Resources

University of Pennsylvania – a detailed biography and access to digital editions of her major printed works:

http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/hemans/biography.html

University of Maryland - Romantic Circles – a refereed scholarly Website devoted to the study of Romantic-period literature and culture:

http://www.rc.umd.edu/

This includes an excellent critical analysis by Nanora Sweet and Barbara Taylor of The Sceptic: A Poem:

http://www.rc.umd.edu/editions/sceptic/contents.html

San Jose State University – an attractive Hemans website with a brief biography, images, sample poems and criticism:

http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/harris/StudentProjects/Kim/index.html

University of Montreal - Romanticism on the Net – an International Refereed Electronic Journal devoted to British Romantic studies with occasional articles on Hemans:

http://www.ron.umontreal.ca/

The Victorian Web – a good page on Hemans with links to online texts:

http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/hemans/index.html

Select Bibliography

Clarke, Norma. Ambitious Heights: Writing, Friendship, Love—The Jewsbury Sisters, Jane Carlyle, and Felicia Hemans. (Routledge, 1990).

Cochran, Peter. “Fatal Fluency, Fruitless Dower: The Eminently Marketable Felicia Hemans.” Times Literary Supplement, 21 July 1995.

Feldman, Paula R. ed. Records of Woman: With Other Poems. (University Press of Kentucky, 1999).

Feldman, Paula R. ed. British Women Poets of the Romantic Era. (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001).

Feldman, Paula R. and Theresa M. Kelley, eds. Romantic Women Writers: Voices and Countervoices. (University Press of New England, 1995).

Feldman, Paula R. “The Poet and the Profits: Felicia Hemans and the Literary Marketplace.” Keats-Shelley Journal 46 (1997): pp148-76.

Kelly, Gary. ed. Felicia Hemans: Selected Poems, Prose, and Letters. (Broadview, 2002).

Lootens, Tricia. “Hemans and Home: Victorianism, Feminine ‘Internal Enemies,’ and the Domestication of National Identity.” PMLA 109:2 (March 1994). pp238-253.

Mellor, Anne. Romanticism and Gender. (Routledge, 1993).

Pettit, Claire. “Our sweet Mrs Hemans.” Times Literary Supplement, 15 September 2000.

Ross, Marlon B. The Contours of Masculine Desire: Romanticism and the Rise of Women's Poetry. (Oxford University Press, 1989).

Rossetti, W. M. “Prefatory Notice.” The Poetical Works of Mrs. Hemans. ( Moxon, 1873)

Sweet, Nanora and Julie Melnyk, eds. Felicia Hemans: Reimagining Poetry in the Nineteenth Century. (Palgrave, 2001).

Trinder, Peter W. Mrs Hemans. (University of Wales Press, 1984).

Wilson, Carol Shiner, and Joel Haefner, eds. Revisioning Romanticism: British Women Writers, 1776-1837. (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994).

Wilson, Frances. “The Italy of Human Beings.” London Review of Books, 16 November 2000.

Wolfson, Susan J. ed. Felicia Hemans: Selected Poems, Letters, Reception Materials. (Princeton University Press, 2005).

Wu, Duncan. Romantic Women Poets: An Anthology. (Blackwell Publishing, 1997).

|