THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

Series One: The Papers of Sir Hans Sloane, 1660-1753 from the British Library, London

Part 4: Alchemy, Chemistry and Magic

Alchemy was still a vibrant discipline during Sir Hans Sloane's lifetime. Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727), the greatest scientist of his generation, undertook alchemical experiments, and the subject blended both proto-chemistry and pharmaceutical research. Alchemy could claim a 3,700 year heritage, having been established by the great Arabic and Greek philosophers of antiquity, and was refined and developed by successive generations of scholars including Thomas Aquinas and Roger Bacon. Amongst its greatest achievements it could claim the discovery of the mineral acids (hydrochloric, nitric and sulphuric acid) and the invention of the processes of sublimation and condensation. It also pioneered much of today's laboratory equipment.

The goal of alchemy was nothing less than the attainment of wealth, longevity and immortality. By reducing and recombining substances it aimed to transform base metals into gold and to produce a powder or pill to cure every sickness.

Sir Hans Sloane's collection of alchemical manuscripts is one of the finest in the world and enables scholars to trace the history of the subject from c1900BC to c1600AD, charting its developments and setbacks, and its association with astrology, chemistry, magic and the occult. We include a total of 137 manuscripts dating from the 12th to the 17th centuries, featuring works by 30 key authors.

The earliest writer represented is the legendary Egyptian leader who was known as Hermes Trismegistus by the Greeks, and reputed to have lived c1900BC. We cover 20 manuscripts with works attributed to him including 3 versions of the Tabula Smaragdina (the Emerald Tablet), the foundational text of alchemy.

The discovery of mercury in c300BC provided further impetus to the discipline that the Greeks called Alchemy (al chemeia) in honour of the Egyptians. We feature 16 manuscripts containing works attributed to Aristotle (384-322BC), whose teachings - particularly the Secreta secretorum and Liber perfecti magisteri Alchemia - were still being studied 1,800 years later. Anaxagoras and Synesius (c300AD) are also featured.

The great Arabic authorities of the 8th-11th centuries are also well represented. Geber, or Jabir ibn Haiyan (Al-Tarsusi), has not been firmly identified but flourished around c760AD. His summa perfectionis has been described as "the main chemical textbook of medieval Christendom." ◊ Geber authored many famous works such as the liber fornacum (the book of furnaces), de investigatione perfectionis (on the investigation of perfection) and de inventione veritatis (on finding out the truth). All are included among the 13 manuscripts containing works attributed to him in this collection. His chief preoccupation was to provide a theory for the generation of metals for which he sought the al-iksir (or elixir).

Rasis, or Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariyya Al-Razi (c825-c925), is featured in 14 manuscripts and Avicenna, or Abu Ali ibn Sina (980-c1036) in 10. Rasis made the distinction between bodies (metals) and spirits (sal ammoniac, mercury and sulphur) and gained a reputation for his practical experiments. Avicenna was revered as one of the great medical authorities well into the Middle Ages, concentrating on the development of drugs to combat illness.

Arabic learning in the field of Alchemy gradually spread to continental Europe. As early as the 4th century BC, Morienus from Rome, represented by 3 manuscripts in this collection, went to Alexandria to learn from Adfar. His writings were translated into Latin in 1144 by Robert of Chester, unleashing a surge of interest in alchemical texts. Gerard of Cremona (c1150), represented by 4 manuscripts, was also important in introducing the works of Avicenna and Rasis to Spain.

Thirteenth century alchemy was dominated by the three doctors - Doctor Universalis, Doctor Mirabilis and Doctor Illuminatus.

Doctor Universalis was the name given to Albertus Magnus (c1200-1280), a Dominican Friar whose alchemical treatises are substantially covered in 13 manuscripts covering 20 texts, including seven versions of the Semita recta (the right path, also known as Libellus de alchima), De alchimia and Compositum de composites. His pupil, Thomas Aquinas (1225/7-1274), continued his work exploring the science of matter and the composition of things and we feature 3 alchemical manuscripts attributed to Aquinas.

Doctor Mirabilis was Roger Bacon (c1220-1292), a Franciscan Friar born in Ilchester, Somerset. Bacon explored the properties of aqua fortis (nitric acid), aqua vitae (alcohol), mineral salts and acids. He also understood the importance of air to combustion and learned how to purify saltpetre through crystallisation. Much of his work and theory relating to alchemy is captured in his speculum alchemiae (the mirror of alchemy), radix mudi (the root of the world) and tractatus triumverborum (the treatise of three words). He also wrote De mirabilis potestate artis et naturae (on the wonderful power of art and nature) which predicted flying machines, submarines and high speed horseless cars. All of these writings are included in 21 manuscripts, covering 37 texts, making this an extremely important resource for Bacon scholars.

Doctor Illuminatus was Ramon Lull (c1220-1292) who is also significantly represented with 23 manuscripts covering 70 texts. Based in Palma, Majorca, he worked closely with Arnald of Villanova (c1240-1311), a Catalan physician, for whom we have 23 manuscripts covering 31 texts. In De lapide philosophorum (on the philosopher's stone) and Rosarius philosophorum (the philosopher's rosary - which is cited in Chaucer's Canon's Yeoman's Tale – three copies of which are found here) he sets out to describe the transmutation of metal into gold and Lull is said to have learned the secret from him. It was for this reason that Lull was encouraged to come to England to meet King Edward II and it is said that he transmuted 50,000 pounds worth of gold to finance the crusades. He was later imprisoned, but escaped and died in Asia.

Another scientist who is said to have discovered the philosopher's stone is Nicholas Flamel (1330-1418), so it is appropriate that he should be remembered in the first Harry Potter book for exactly this feat. To lend credence to his claims it is known that the Paris notary lived to a great age and died wealthy. He is featured in 3 manuscripts in this collection.

George Ripley (early 15th century - c1490), Canon of Bridlington, was born near Harrogate and continued the English tradition in alchemy. A devotee of Lull, he is also alleged to have manufactured gold for the Knights of St John. His works include De lapide philosophorum, seu de phenice (on the philosopher's stone or on the phoenix) and Medulla alchemiae (the marrow of alchemy). We include 27 manuscripts attributed to him, covering 62 works.

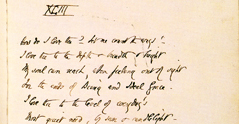

Thomas Norton (c1433-1513/14) was said to be Ripley's heir and devoted himself to the search for the elixir of life. His most important work was the Ordinal of Alchemy and we include 10 manuscripts of this key text including one dating from the end of the 15th century (he began the work in 1477). This text was translated into German by Michael Maier.

Paracelsus, or Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim (1493/4-1541) dominated European alchemy in the 16th century, largely as a result of his abilities as a self-publicist. He also accelerated the move of alchemy into pharmaceutical research, offering a prodigious array of pills and potions to replace the traditional herbs of healers. We include 6 manuscripts attributed to him, containing 25 works.

Thomas Charnock (1526-1581) is the latest major figure in the History of Alchemy covered in this collection. Born in Faversham, Kent, he moved to Combwich, Somerset, to practice his art. We include a holograph text of A book of philosophie, as well as a roll contatining Lullian diagrams, and two further manuscripts.

In addition to the 21 major authors already described there are many works by anonymous writers and many intriguing works attributed to Merlin (5 manuscripts), Miriam the prophetess (3 manuscripts), Nostradamus (1 volume containing prophecies), Pearce the Black Monk (8 copies of his verses on the elixir), Sahl ibn Bashir, King Salomon of Israel (9 manuscripts), Robert Lombard (on magic), Jehan de Meung (2 manuscripts), Johan Tritheim (3 manuscripts), John de Rupecissa (7 manuscripts) and John Gower.

Early chemistry can be seen in manuscripts pertaining to Robert Boyle, Marsiglio Ficino and Nicolas Lemery. John Dee's manuscripts have not been included as these are featured in our separate Renaissance Man project. However, we do include a handful of items by Edward Kelley, his sometime associate, and by Arthur Dee, his son.

Other fascinating items include a 17th century catalogue of books relating to alchemy and medicine, followed by a catalogue of books on magic (Sloane Ms 696) and a 15th century herbal with a list of charms against elves, serpents, malignant spirits and the tooth-ache (Sloane 962). Two items on witchcraft are a 17th century miscellany with remedies (Sloane Ms 1783) and an 18th century collection of tracts on witches (Sloane Ms 3943). There is also an account by Simon Forman of magical rings (Sloane Ms 3822).

It is fortunate for scholars today that Sir Hans Sloane followed Nicholas Flamel's habit of hoarding books on alchemy, magic and the occult. This collection - spanning the entire history of alchemy - will enable us to better understand the development of theoretical and practical chemistry, the early acceptance of elementary and particle physics, and the emergence of pharmaceutical medicine.

◊ George Sarton, Introduction to the History of Science, Baltimore, 1927-1948.

|