MICHAEL FIELD AND FIN-DE-SIÈCLE CULTURE & SOCIETY

The Journals, 1868-1914, and Correspondence of Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper from the British Library, London

(Add Mss 46776-46804, 45851-45856 & 46866-46897)

EDITORIAL INTRODUCTION

By Dr Marion Thain, Department of English, University of Birmingham

This microfilm facsimile copy includes the 30 volumes of diary material of ‘Michael Field’, together with 8 bound volumes of correspondence between Michael Field and others, held in the British Library. (1)

Michael Field was an aunt and niece couple who not only published poetry and drama under the single male pseudonym, but who also lived their lives through that name, among other sobriquets. Katharine Bradley, the aunt (1846-1914), was known primarily as ‘Michael’ to her friends, but was also commonly called Sim by her lifelong companion and niece, Edith Cooper (1862-1913). Cooper was known primarily as ‘Henry’ or ‘Field’, but other names proliferate in the diaries. The name ‘Michael Field’ is therefore a bipartite name, signifying the assumed names of two separate women, as well as appearing to signify one single male identity: Bradley and Cooper used the composite single name ‘Michael Field’ to represent their unity in both literary and personal arenas. The two women were everything to each other. When Cooper’s mother was invalided after the birth of her younger sister, Bradley stepped in and took on the role not only of aunt but also of guardian and teacher; soon the two women were also filling the roles of mother and daughter, sisters, literary collaborators, and, eventually, lovers. In 1884 (when Cooper was 22, and Bradley 38) they published their first work in the name of Michael Field - the verse-drama Callirrhoë. From then on their lives became intertwined in the identity of Michael Field.

Bradley and Cooper’s life-narrative, recounted in both letters and diaries, is split along some very dramatic fault-lines. The early conversion to Paganism (on the acquisition of a pet Skye Terrier) was mirrored by an equally cataclysmic conversion to Catholicism (on the death of a pet Chow dog, much later on in their lives). It is a life-story with a dramatic tripartite structure in which the protagonists are involved in key moments of transition. The story of Michael Field is based around a complex and compelling personal mythology, but there is a danger of only ever labelling Bradley and Cooper as eccentric, and seeing the madness of their personal symbolism, and never seeing their story as engaged fully with the major issues of the period. Rather, their lives display a thorough engagement with the late-Victorian and early twentieth-century world, both in terms of the people with whom they associate, the issues with which they are concerned, and also in the manner in which they choose to construct their narrative. In their work we often see ingenious and unusual approaches to paradigmatic turn-of-the-century concerns.

The Diaries

There is no autobiography of ‘Michael Field’ as such, but the life-story of the two women is represented in the 28 large volumes of diaries which they co-wrote. The diary is (except for an anomalous first volume) specifically the diary of Michael Field, not that of Edith Cooper and Katharine Bradley, and begins in 1888 when Edith was 26 and Katharine 42, after they had established their dual identity. The first volume of the diaries is an exception, written by Bradley on her own during an extended trip to Paris in 1868-9. This narrative is dominated by the death of Alfred Gérente, the brother of her friend, to whom she had formed a passionate romantic attachment. Volumes 2 to 29 cover the years from 1888 to Katharine’s death in 1914, and bear the title ‘Works and Days’, inscribed in the front of volume 2. Volume 30 contains miscellaneous, loose material collected from vols. 1-28 into two separate folders.

In Bradley and Cooper’s published drama and poetry, the pseudonym can be understood, at least initially, as a deliberate ploy to persuade the general public that they are receiving work from a single male author (and the function of the pseudonym in the published work is much discussed by critics (2)), but in the diaries that are reproduced here, the name has no such function. In their life-writing, the women’s self-creation through this sobriquet expresses their unity, but it does not efface their distinctness: the diaries do not pretend to record the life of a single male, as two different hands record the experience of two clearly differentiated personas. Clearly the name ‘Michael Field’ was much more than a literary pseudonym: it was an expression of their actual, lived, identity.

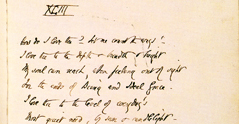

The diaries are hardbound, scrapbook-size volumes, bound with dark blue board or vellum. Even after disregarding the typed indexes and the pencil-marked editorial comments left by Thomas Sturge Moore (Michael Field’s literary executor) when he edited the text into the selected published volume, Works and Days (3), one is left with a carefully constructed set of diaries which were clearly conceived of by the authors as constituting a book rather than simply a repository for odds and ends and personal reminders. The first volume of the Michael Field diary proper (1888-89) has the title of the whole work – Works and Days – added retrospectively, squeezed in at the top of the first page, above the first line of text which had been written on the top printed line of the page. At some point the women have gone back with a red pen and used it to organise the volume, adding other subtitles to the volume in the same red ink – such as ‘French Books’ heading a list at the back of this volume of French titles. The point at which they went back and added the title they had chosen for the work to the top of the first page of text is a point at which they certainly conceived of the diary as a ‘work’: a whole, potentially public, narrative.

The ‘work’ however, is not just made up of handwritten text by the two women, in two different hands. The volumes contain a mixture of textures: of newspaper cuttings; rough and fair copy of poems; pressed flowers; copied-out letters from correspondents; transcriptions of letters sent to others; or pasted-in cuttings of poems. The texture of the journals would have been even richer before much of the loose-leaf material was taken out and placed in a separate folder (volume 30). Newspaper-clippings play a particularly interesting role in diaries because they situate the writer directly in relation to a shared public world and they allow the author to view happenings – sometimes events to which they are very close – through the eyes of the general public. (4) This is particularly true of Bradley and Cooper’s response to Robert Browning’s illness and death (vol. 2 [1888-9], 121-2). While he was a great personal friend they still include the newspaper reports which chart his demise. This is partly because Browning grew ill in Venice, far from home, so the newspaper reports surely indicate the physical distance from which Bradley and Cooper viewed the whole event, but this is also perhaps partly a means of displaying their connection with a level of national literary fame of which they desperately wanted to be a part and to which they might have felt connected through the coverage of Browning’s death.

Bringing into the diaries transcriptions of their correspondence allows other voices into their text in order to dramatise it and bring it to life, but the letters also connect their lives with an external network of characters. This has the effect of placing the women within a more public arena even in this most personal of genres. Incidents of particular importance to them are often retold multiple times from different perspectives in the diaries by way of their inclusion of other voices and layers in their narrative. For example, just after the death of their beloved pet Chow dog, Bradley and Cooper copy into the diary a letter they have written to Marie Sturge Moore. This brings in a specific, external, audience to their tragedy, and allows the events of the past few days to be narrated again in the diary, for her benefit. Yet within this letter we also hear the voices of characters from Bradley and Cooper’s home-life who add a further commentary on their personal grief:

"The boy who for seven years has served us writes ‘He [the Chow dog] was your only + dearest friend you had at Paragon.’ + our landlord here said simply when we spoke of our grief ‘why, of course, he was your all.’ "

(vol. 20 [1906], f20)

The servant boy and the landlord people this narrative as ‘extras’ who act as an internal audience for Bradley and Cooper’s drama, mediating between the personal experience and the more public expression of it in the letter to Marie. A little further on in this volume Bradley and Cooper express anger at Charles Ricketts’ letter to them which made fun of their excessive grief over the death of the dog (f25). We then get a passage which directly addresses Ricketts (in Bradley’s hand), and which we must assume is another transcript of a letter, even though it is not identified as such explicitly. Another voice is thereby added to the dramatisation of this incident. This multiplicity of voice adds a significantly new dimension to the events of the past few days and by including Ricketts’ jarring voice, Bradley and Cooper are forced into further acts of reflection and self-interpretation. In including this letter justifying her grief to Ricketts, Bradley is also explaining it to a potentially broader audience of the diary.

But for whom was the diary of Michael Field written? We know that Bradley and Cooper discussed with Thomas Sturge-Moore the possibility of his editing their diaries after their death – which he eventually did, bringing out the published, and much abbreviated, volume in 1933. So Bradley and Cooper certainly, at some point, began to consider their journals as items for the public domain. Internal markers suggest that they conceived of the diaries as semi-public documents from a very early on. As I have already indicated, these diaries are quite crafted pieces of text, and not simply personal reminders. The ‘truly private diary’, as defined by Lynn Z. Bloom, is written in a way which allows for ‘neither art nor artifice, they are so terse they seem coded’: while they may give the bare bones of the writer’s life, they lack the narrative dimension of biography or autobiography. (5) What Bloom calls ‘private diaries as public documents’, on the other hand, are much more like self-conscious works of art in their use of narrative techniques and the inclusion of contextual information to help the external audience. Diaries that have been written with an audience in mind are sufficiently developed to be self-contained and more or less self-explanatory. Thus the indication of any tidying up of the work at a later date, such as I have already remarked upon in the Michael Field work, is one factor which clearly points to some kind of public intention. Similarly, the kind of dramatisation of a narrative, peopled with voices, as described above, is another marker of a level of craftsmanship which indicates an expectation of an audience. Of course this example of diary writing is complicated by the fact that it could never be a truly private work, at least not in any conventional sense, because the two women were each other’s audience and Bradley and Cooper wrote it primarily for each other’s eyes. The diary was always, therefore, bound to be a literary project for the two authors to some extent, and we should not be surprised at its fulsome and crafted narrative aspect.

Such qualities in a diary inevitably provoke questions about its potential role as autobiography. Robert Fothergill gives us the term ‘serial autobiography’ to denote those diaries, of ‘a particular and well-developed type’, which are best regarded as a synthesis of the diary and autobiographical format. (6) Such ‘serial autobiography’ entails the diarist feeling under obligation to bring together a coherent story rather than simply record a random string of events. Two key attributes of autobiography usually thought lacking in the diary are retrospection and introspection (7); these are seen as the product of a privileged vantage point acquired only towards the end of the life. In serial autobiography, however, the diarist manages, through various strategies, to use both qualities to structure the narrative. This is entirely congruent with the thought of one nineteenth-century autobiographical theorist, Wilhelm Dilthey, who considers retrospection and introspection to be part of any present moment of reflection and not only the benefit of a final, or near-final, perspective. Writing about Geothe’s Dichtung und Wahrheit, Dilthey claims:

"… a man looks at his own existence from the standpoint of universal history. ... he experiences the present as always filled and determined by the past and stretching towards the shaping of the future: thus he feels it to be a development." (8)

In fact, Dilthey’s writing on autobiography never addressed the conventions of auto-biography as a written form, defining it rather as the understanding of oneself. (9) For these reasons it is illuminating to consider Bradley and Cooper’s serial life-narrative with reference to a late nineteenth-century conception of autobiography.

Moreover, Bradley and Cooper’s diary narrative does, towards its end, move towards the structure of a spiritual autobiography – the dominant mode of autobiography by the start of the nineteenth century. (10) This genre of personal account was structured around a tale of youthful depravity and dramatic conversion, and can be seen to be the structure that Bradley and Cooper’s narrative assumes during their conversion to Catholicism in 1907. At this time, in the letters and the diaries, Bradley and Cooper struggle to come to terms with past events and show a tendency to reinterpret them in light of the conversion, and to fit them into a narrative of spiritual progression.

While comprising a developed narrative, which can usefully be viewed in relation to various contemporaneous models of autobiography, the diaries of Michael Field simultaneously provide a fascinating challenge for influential paradigms of life-writing. Phillipe Lejeune’s definition of the ‘autobiographical pact’ which relies on the proper name as the guarantee of ‘a contract of identity’ (11), for example, is clearly questioned by this example of dual authorship presented under a single, male, sobriquet. This example presents quite a different challenge to that usually posed by the adoption of a pseudonym: if Bradley and Cooper were simply pretending, in the diary, to be one man the work would fail, as a piece of autobiographical writing, simply by being about the wrong person. As it is, this sincere, but unusual framework for life-writing must be seen to test the boundaries laid out in prominent critical thinking on this issue.

Correspondence

The story told though Bradley and Cooper’s letters cannot be separated from that represented in the diary. Not least because some of the hundreds of letters they wrote over the course of their lifetime are interwoven with the diary in a very literal way. But the letters also amplify, retell, and sometimes contradict the story told in the diary. This resource charts, more directly than the diaries, Michael Field’s interaction with the outside world, placing them within a network of connections that define their place in the fin-de-siècle literary and artistic community. In these letters we see at first hand how well-known figures reacted to them and their work – sometimes writing with praise, sometimes to reject an unsolicited manuscript, sometimes writing to someone they believe to be a single male author, often addressing the women as Michael and Henry with an ease which suggests an unproblematic acceptance of their masculinised identity.

The sheer bulk of their correspondence with certain figures indicates where their main friendships and day-to-day support lay. Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon were one such source of support, providing a role-model for the kind of same-sex artistic relationship that Bradley and Cooper were developing. Father-Mentor figures such as John Ruskin and Robert Browning were also clearly extremely important to them. The two John Grays held a particular place in their affections. The correspondence with John Miller Gray – curator of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, and art critic, and a literary reviewer – occupies two volumes here, while the lengthy exchange of letters with the other John Gray – the decadent poet turned Catholic priest – is represented in holdings in the National Library of Scotland, and alerts us to the fact that the British Library collection reproduced here is not entirely representative of Michael Field’s circle of acquaintance.

As well as these deeper friendships, one can trace in this correspondence contact with some of the major literary and cultural figures of the day, with volume 8 bearing the names of Matthew Arnold, Havelock Ellis, Richard Garnett, W. M. Rossetti, J. A. Symonds, and Arthur Symons, amongst others. There are relatively few letters to or from women in this collection (Sarianna Browning being a notable exception), and it seems that Bradley and Cooper’s search for patronage drew them more to men than women, even though they knew and had contact with other women writers of the period. Moreover, sometimes there was something more than patronage at stake. The correspondence with Bernard Berenson, when read alongside relevant entries in the diary, tells the highly charged and disturbing story of Cooper’s unrequited love for him which resulted in her physical sickness on more than one occasion (see particularly the letters and diary entries from the start of 1895). This incident reminds us that the women’s sexuality cannot easily be contained solely within a modern conception of lesbianism and that while their love for each other was the romance central to Michael Field, they both formed passionate romantic attachments to men over the course of their lives.

NOTES

1 While all the volumes of correspondence held in the British Library under the name of Michael Field are reproduced here, this does not represent every correspondence involving Michael Field held in the British Library. Letters by Michael Field are also contained within archives of papers indexed under the name of the other correspondent (for example that Sydney Carlyle Cockerell, George Bottomly, and, most significantly, that of Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon [see Ricketts and Shannon papers vols. 3-5]), which cannot be included here.

2 See, for example: Virginia Blain’s ‘“Michael Field, the Two-Headed Nightingale”: Lesbian Text as Palimpsest’, Women’s History Review 5 (1996): 239-257; Holly Laird’s ‘Contradictory Legacies: Michael Field and Feminist Restoration’, Victorian Poetry 33 (1995): 111-127; Yopie Prins’ ‘A Metaphorical Field: Katherine Bradley and Edith Cooper’, Victorian Poetry 33 (1995): 129-148; Chris White’s ‘“Poets and Lovers Evermore”: Interpreting Female Love in the Poetry and Journals of Michael Field’, Textual Practice 4 (1990): 197-212.

3 Works and Days: From the Journal of Michael Field (with introduction by Sir William Rothenstein), eds. T. & D. C. Sturge Moore (London: John Murray, 1933).

4 In ‘Textual Boundaries: Space in Nineteenth-Century Women’s Manuscript Diaries’, Cynthia A. Huff reflects on how the ‘inclusion of extra-textual material, such as drawings, newspaper clippings, official letters, and other’s poems and observations’ modifies or extends the spatial boundaries of the diarist’s own written account (Inscribing the Daily: Critical Essays on Women’s Diaries, ed. Suzanne L. Bunkers and Cynthia A. Huff [Amherst, University of Massachusetts Press, 1996], 124).

5 Lynn Z. Bloom, ‘ “I write for Myself and Strangers”: Private Diaries as Public Documents’, Inscribing the Daily: Critical Essays on Women’s Diaries, ed. Bunkers and Huff, 25.

6 Robert A. Fothergill, Private Chronicles: A Study of English Diaries (London, Oxford University Press, 1974) , 152.

7 See Linda H. Peterson’s discussion in Victorian Autobiography: The Tradition of Self-Interpretation (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1986), 125.

8 H. P. Rickman (ed. and trans.) Wilhelm Dilthey: Selected Writings (Cambridge University Press, 1976), 214.

9 See Laura Marcus’s discussion of Dilthey in Auto/biographical Discourses: Theory, Criticism, Practice (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1994), 142-3.

10 See Linda H. Peterson, Victorian Autobiography, 3.

11 Philippe Lejeune, ‘The Autobiographical Pact', in On Autobiography, ed. Paul John Eakin, trans. Katherine Leary (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989).

|

|