NEWSLETTERS OF RICHARD BULSTRODE, 1667-1689

From the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas, Austin

"The French King has expressed great inclinations to make the peace ..." 31 March 1668.

An announcement such as this, based on first-hand reporting from across Europe, could have important implications for a leading member of a noble family in metropolitan or rural England. Such news could impact trade; open up opportunities at Court; or suggest a change in the political climate requiring immediate response.

During the sixteenth century an ever more sophisticated group of journalists arose to supply this news, leading, eventually, to the creation of the first newspapers. Each journalist depended on a network of contacts to supply the news and a list of subscribers to pay for the service. Instead of being directly in the pay of a single patron to whom they would write a personalised letter, the journalists employed clerks to replicate their daily bulletin to dozens of customers. To the subscriber this still felt like a bespoke service. The newsletters they received were handwritten and addressed directly to them. Occasionally they carried additional information known to be of interest only to them.

With the proliferation of printing, printed newsletters and news-books also began to compete in the market for news. They had the clear advantage of cutting out the costly labour of copying by hand, but were not able to report some news due to worries about its sensitivity. Equally, they were not able to report on the votes or proceedings of the Houses of Parliament without authorisation.

The leading newsletter offices began to gain a certain independence and power. Inevitably, they drew upon the knowledge of the diplomatic corps and intelligence services, not just of England, but across Europe. For instance, in return for the latest news from London, Abraham Castelyn, founder of the Haarlem Gazette in the Netherlands, shared his news on European wars and the rise of the House of Orange.

By the mid-1660s, one of the leading publishers of newsletters in London was undoubtedly Sir Joseph Williamson (1633-1701). The son of a vicar, he was born in what is now Cumbria in Northwest England, and educated at Westminster School and Queen’s College, Oxford, where he became a Fellow. His move into politics came in 1660, when he was taken on by Sir Edward Nicholas (1593-1669).

Nicholas was also an alumna of Queen’s, who had risen to power under Charles I as the prime mover of the levy of ship money and the King’s chief informant on Parliamentary business. Nicholas was appointed Secretary of State, 1641-1646, and his dealings at the capitulation of Oxford (15 May - 24 June 1646) during the Civil War were skilful enough that he was granted permission for his family’s withdrawal to France. In 1654, whilst in exile, Charles II re-appointed Nicholas as Secretary of State, enabling a smooth resumption of power in May 1660. It was at this point that Williamson joined him. He was exposed to a wide range of royalist contacts in Scotland, France and Spain and to the realpolitik of competing factions seeking to gain favour in government.

When Nicholas stepped down in October 1662, Williamson survived the process and was taken on by Sir Henry Bennet (1618-1685), Nicholas’s successor as Secretary of State of the Southern Department1, who swiftly became the King’s favourite. Bennet was educated at Westminster School and Christ Church, Oxford. He fought for the Royalists during the Civil War, gaining a prominent scar on the bridge of his nose, and during the Protectorate he served the Court in Exile in Madrid. Bennet (created the Earl of Arlington in 1663) served as Secretary of State from October 1662 to September 1674 and played an active role in foreign affairs. He was directly involved in the secret Treaty of Dover (1670) with Louis XIV of France, which pledged England’s conversion to Roman Catholicism and the abandonment of the Triple Alliance with Sweden and the Netherlands. This led to the Third Anglo-Dutch war, 1672-1674, ending in the Treaty of Westminster, which passed New York and New Jersey to English control. Bennet was also involved in intrigues against Ormonde and Clifford, and in attempts to restore absolute power to Charles II.

During this period, Williamson served as Bennet’s Under-Secretary and was active in newsgathering. He was involved from 1663 with Roger L’Estrange (1616-1704) in the development of the Public Intelligencer and The News and this also brought him into contact with Henry Muddiman (1629-1692), one of the most prolific journalists of the age with a widespread network of foreign contacts. As it became clear that newsletters were a valuable source of information and income, the three vied with each other for supremacy. Williamson used Muddiman and his list of contacts to marginalize L’Estrange, and helped to found the London Gazette. This was first published on 7 November 1665 and is recognized as the oldest surviving English newspaper, carrying statutory and official notices. By 1666, Muddiman had left to establish a rival news operation publishing the Current Intelligence, under the patronage of Sir William Morice (Secretary of State for the Northern Department, June 1660 – Sept 1668). Williamson’s newsletters continued and were often issued together with a copy of The London Gazette, as can be seen from traces of newsprint on some of the letters.

Bennet’s enemies conspired against him and he was impeached by Parliament in January 1674. Even though he escaped the charges, he was forced to resign as Secretary of State in September 1674 and was replaced by Henry Coventry (Secretary of State for the Southern Department, 1674-1680). Once again, Williamson escaped the fall of his superior and was made Secretary of State for the Northern Department, September 1674 – February 1679. These years witnessed the French victory at the battle of Turckeim (5 Jan 1675) against Prussian and Austrian forces; the Virginia rebellion of 1676; the marriage of Mary (daughter of the Duke of York, the future James II) to William of Orange in 1677; the Swedish victory at the battle of Rostock (1677) defeating the Danes; the Peace of Nijmegen (10 Aug 1678), ending the war between France and the Netherlands; the ‘Popish Plot’ of Titus Oates (6 Sept 1678); the passing of the Habeas Corpus Act (1679) and the failure of the ‘Exclusion Bill’ aimed at preventing the succession of James II. Williamson’s resignation was due to his alleged involvement in the Popish plots, but he was acquitted by Charles II.

In 1677 Williamson was made the second President of the Royal Society, a position he held until 1680, when Sir Christopher Wren succeeded him. Williamson’s interests were more of an antiquarian than a scientific nature, but the position did open up further contacts.

He kept a fairly low profile during the accession of James II in 1685, the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688, and the War of the Grand Alliance, 1688-1697, between France and the League of Augsburg, which consisted of Emperor Leopold I, various German princes, Sweden, Spain and the Netherlands. England joined the alliance in 1689 due to William II’s animosity towards Louis XIV.

In 1697 he returned to the political scene, when he represented England at the Congress of Ryswick. In 1698 he was a signature to the treaty for the partition of the Spanish Monarchy. He died at Cobham, Kent, on 3 October 1701, leaving a fortune of over £13,000. £6,000 and his library were bequeathed to Queen’s College, Oxford.

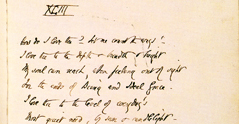

The c1500 Bulstrode Newsletters at the University of Texas span the period from 1667 to 1689 and primarily emanate from Joseph Williamson’s news office, although there are some 235 written from Edward Coleman’s news office. For a period of twenty-two years (excepting 1684 and some gaps) they provide a privileged, weekly analysis of parliamentary business, foreign affairs and other important happenings.

All bar 80 of the letters were written to or intended for Sir Richard Bulstrode (1610-1711). Educated at Pembroke College, Cambridge, and a member of the Inner Temple, Bulstrode served with the Royalists in the Civil War, first with the Prince of Wales’s regiment, then as Adjutant-General of Horse, then as Quartermaster-General. He was also responsible for Strafford’s funeral. In 1673 he was appointed ‘Agent’ of Charles II at Brussels, and following his knighthood in 1675, he was made ‘Resident Agent’. In 1685, following the accession of James II, he became ‘Envoy’. Following the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688, he followed James II into exile to the court of Saint-Germain, where he died in 1711. As the saleroom catalogue description of the newsletters, which follows, makes clear, he was “a valued correspondent of Williamson’s office.” He was well placed to report on the latest events in the Low Countries, and also gathered information from Vienna and Venice.

These newsletters are a crucial source for anyone studying the reigns of Charles II and James II and provide an important supplement to the State Papers of the period.

1 The Secretary of State of the Southern Department had responsibility for Southern England, Wales, Ireland, the American colonies and England’s relations with Roman Catholic and Muslim states. The role was considered superior to that of the Secretary of State for the Northern Department, who had responsibility for Northern England, Scotland, and relations with Protestant states.

|