NIGHTINGALE, PUBLIC HEALTH AND VICTORIAN SOCIETY

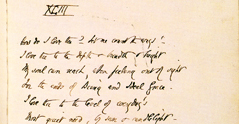

from the British Library, London

Part 4: Correspondence with nursing staff and papers relating to St Thomas’s Hospital and other subjects

Lynn McDonald

Department of Sociology and Anthropology,

University of Guelph

Editor of The Collected Works of Florence Nightingale

From an early age Florence Nightingale (1820-1910) knew that her life was to be dedicated to nursing and the welfare of the sick. At the age of sixteen she experienced a ‘call to service’, but nursing was at that time a low-class ill-paid occupation and Nightingale’s family would not permit her to take up her calling. Her determination eventually won through when she was given permission to lead a group of nurses to the Crimea to care for the sick and wounded soldiers. Reports of Nightingale’s ceaseless work reached the public’s attention and admiration, and on her return home in 1856 Nightingale was feted by Victorian society. Nightingale intensely disliked her status as a heroine but she found it was to prove useful in getting attention and support for her work, and through an impressive network of politicians, government officials, and journalists she was able to effect pioneering nursing and hospital reform. Nightingale’s concern was for all classes of society: for the poor sick in the workhouses, the ordinary soldier in the military hospital, as well as those in civil hospitals. Today Nightingale is remembered as the major founder of the modern nursing profession, and for her contribution to a public healthcare system based on health promotion and disease prevention.

The microfilm series, Nightingale, Public Health and Victorian Society details the life and work of Florence Nightingale and is sourced from the British Library. Our Consultant Editor for this series, Dr Lynn McDonald describes this collection as, “the largest and most diverse collection or original material by Florence Nightingale in the world”. The archive features Nightingale’s letters, papers, manuscripts and books. Nightingale wrote letters almost every day of her life and for many of the original letters there are also the drafts and copies of her correspondence.

Part 4 covers Nightingale’s work with the nursing profession. Lynn McDonald says “Her pioneering work in bringing professional nursing into the workhouse infirmaries, a major step towards the achievement of a public health care system, has received little scholarly attention. This required careful political manoeuvring as well as nursing expertise, and is a fascinating story as it unfolds”. This story can be followed in this collection of manuscripts.

This part consists of Nightingale’s correspondence with key nursing figures, not only at St Thomas’s Hospital, where the Nightingale Training School was based, but also in hospitals and other nursing institutions throughout Britain and the world. As well as founding the Nightingale Training School she was also involved in establishing the East London Nursing Society (1868), the Workhouse Nursing Association and National Society for Trained Nurses for the Poor (1874) and the Queen’s Nursing Institute (1890).

At the beginning of the nineteenth century hospital nurses were uneducated

working-class women whose main tasks consisted of cleaning patients, making beds, emptying slops and making poultices. Most nurses worked a 16 hour shift and had no paid time off. They had no space of their own, they cooked over the ward fire and slept in the attics, cellars and sometimes in the wards with the patients. Most of the nurses were illiterate and considered unrespectable, being prone to drunkenness. In charge of them was a housekeeper who usually came from the lower middle class. She was not a nurse and was only responsible for order and discipline among the nurses.

However by the end of the century thanks to Nightingale and the training of nurses at the Nightingale Training School the profession and its status in society had changed beyond recognition. Ordinary nurses were trained and had become respectable workers and the matron was a trained nurse of the upper classes whose chief responsibility was to train the nurses and make sure they provided good patient care. Professional nursing was available to all on a par with that available at fee-paying hospitals.

The Nightingale Training School for nurses at St Thomas’s Hospital was founded by Nightingale in 1860 and nurses trained there were sent to hospitals across Britain and abroad. Nightingale care consisted of orderly, disciplined female controlled nursing which emphasised hygiene and moral as well as physical cleanliness. Nurses consisted of less educated working class women who entered as lay sisters who would receive a small amount of money on completion and placement in an institution or home and who were under the control of middle class women who entered as Lady or Special Probationers and became Sisters. The training lasted for one year and the students lived in private rooms with a common social room in a special area of the hospital. They attended classes with an average size of 20-30 students and also looked after the sick at the hospital.

At the end of the 1860s, after a period of leaving the running of the school to the Matron, Mrs Wardroper, Nightingale resumed her interest in the daily work of the school and realised her rules were not being implemented and the Sisters had no control of the probationers. Nor were these women given any opportunity to improve their education and religious knowledge which she believed were essential for the training of a nurse. She therefore began to make efforts to improve the school and made changes to staff. Mrs Wardroper remained, but the apothecary was dismissed and a surgeon was employed to give lectures. Mary Crossland, as Home Sister, was employed and Nightingale herself began to see the nurses on a regular basis and write her famous annual addresses to the probationers.

The correspondence in the Nightingale papers in this part covers key British nursing figures:

- Mrs Sarah Elizabeth Wardroper, Matron of St Thomas’s Hospital, 1857-1894

- Angelique Lucille Pringle of the Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh and Matron of St Thomas’s Hospital, 1872-1909

- Louisa McKay Gordon, Matron of St Thomas’s Hospital, 1890-1900

- Mary S Crossland, “Home-Sister”, 1875-1900

- Sarah Anne Terrot, a former Crimean nurse who worked with Nightingale, 1857-1868

- Mary Jones, Lady Superior of St John’s House Training Institution for Nurses, 1860-1881. She also led the midwifery nurse training programme at King’s College Hospital

- Maria M Machin, Matron of Montreal General Hospital and of St Bartholomew’s Hospital, Smithfield, 1873-1900

- Mary J Pyne, Matron of Westminster Hospital, 1873-1897

- Eva Charlotte Ellis Luckes, Matron of the London Hospital, 1889-1899

- Rachel Williams, Matron of St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington, 1873-1899

- Jane E Styring, Matron of Paddington Infirmary, 1877-1900

- Elizabeth Vincent, Matron of St Marylebone Infirmary, 1873-1901

- Elizabeth Anne Torrance, Matron of Highgate Infirmary, 1869-1877

- Annie E Hill, Matron of Highgate Infirmary, 1872-1877

- Flora Masson, Matron of the Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford, 1889-1897

- Elizabeth Ann Barclay, Lady Superintendent of the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, 1871-1877

- Frances Elizabeth Spencer, Lady Superintendent of the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, 1873-1900

- Jessie Lennox, Matron of Belfast Hospital for Sick Children, 1869-1896

- Agnes Elizabeth Jones, Lady Superintendent of Liverpool Workhouse Infirmary, 1861-1868 (together with extracts from her journal)

- Florence Sarah Lees, afterwards Florence Sarah Lees Craven, wife of Rev Dacre Craven, Superintendent General of the Metropolitan and National Nursing Association, 1868-1900

- Mary Elinor Wilson, Lady Superintendent of Scarborough Ladies’ Convalescent Home, 1868-1870

- Amy Hughes, Superintendent of the Metropolitan and National Nursing Association and of Bolton Workhouse Infirmary, 1891-1901

Also included are drafts of Nightingale’s letters to probationers at St Thomas’s Hospital, 1873-1900, to the nurses at the Liverpool Workhouse Infirmary, 1868 and to the nurses at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, 1872-1873.

Correspondence relating to nursing abroad consists of:

- Correspondence with Sir Henry Parkes, GCMG, Prime Minister of New South Wales, 1866-1892

- Correspondence with Miss Lucy Osburn, (1836-1891), Superintendent of the Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, 1867-1885. Trained at the Nightingale Training School in London Osburn is considered the founder of modern nursing in Australia

- Correspondence with M Amy Turton, Superintendent of the Scuola Infermiera, Florence, 1893-1903

- Letters from Emily (Emmy) Rappe, a Swedish nurse, 1867-1870. She joined the Nightingale School in 1866 and returned to Sweden to take up a post at a new hospital in Uppsala and later became Inspector of Nursing Schools

Also included is Nightingale’s correspondence with medical officers, including surgeon John Croft, 1873-1893, Richard Gullett Whitfield, Apothecary and Resident Medical Officer, 1858-1872 and William Ogle, MD, physician of the Derbyshire General Infirmary, 1864-1891.

We also include letters to other important figures involved in public health reforms whom she could call on for advice and who worked with her behind the scenes.

- William Rathbone, MP, a wealthy Liverpool merchant and philanthropist who worked closely with Nightingale regarding the training of nurses. In 1862 the Liverpool Training School and Home for Nurses was established, from which a district nursing system was begun which spread throughout the country. He was also instrumental with Nightingale in the reform of workhouse infirmary nursing in Liverpool which Nightingale hoped would lead to general reform and later to the abolition of the workhouse system. Papers included here relate to the foundation of the Queen’s Jubilee Institute of District Nursing, 1887

- Surgeon-General Thomas Graham Balfour MD, mostly relating to the Army Sanitary Commission of 1857 and its report of 1858

- Alexander MacGrigor MD relating to his service as Principal Medical Officer and later as Deputy Inspector of Hospitals at the Barrack Hospital at Scutari, 1854-1855

Detailed notes by Nightingale of her interviews with hospital physicians and women concerned with the organisation of district or general nursing, covering 1871-1898 are also to be found in this fourth part as are the interesting notes of her interviews with members of the nursing staff of St Thomas’s Hospital, for the same period.

Miscellaneous memoranda and notes regarding the nursing profession are also included together with those relating to the Royal British Nursing Association and its charter.

This microfilm series featuring the manuscripts of Florence Nightingale held at the British Library provides a resource of great value to those researching nursing, public health, social reform, religion and philosophy in the Victorian period, as well as much important information on India and the Crimea.

|

|