SLAVE TRADE JOURNALS AND PAPERS

Part 1: The Humphrey Morice Papers from the Bank of England

"The prince of London slave merchants ... was Humphrey Morice, ... Member of Parliament, and Governor of the Bank of England...."

Hugh Thomas

writing in The Slave Trade: The History of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440-1870 (New York & London, 1997)

In the nine years between 1721 and 1730 the British carried around 100,000 slaves from Africa to the Americas. The majority of the ships sailed to Africa from London which sent an average of around fifty-six ships a year during 1723-1727, while Bristol sent thirty-four ships and Liverpool eleven.

Humphrey Morice was one of the main slave merchants of London in this period. In 1720 he had eight slave ships, all named after his wife or daughters.

Some of Morice’s vessels were constant traders. The Judith snow made her first voyage in 1721 and her seventh in 1730; the Katharine galley made her first voyage in 1724 and her sixth in 1730, setting a pattern of an annual voyage, and the Portugall galley left on her sixth voyage in 1729. Morice tended to use the same captains, the most famous of whom was William Snelgrave.

He exported from London metal, pewter, brass, swords, guns, beads and textiles and usually loaded a second cargo of goods in Rotterdam of gunpowder, spirits, cloth, brass pans, iron bars, tobacco pipes and knives. He was very keen to sell Dutch goods to Dutch traders in Africa, acquiring gold from Dutch traders in exchange.

His instructions to the captains were explicit and well informed and suggest he preferred to sell the slaves he bought on the Gold Coast to the Portuguese in Africa rather than send his ships across the Atlantic. But if the slaves were not sold in Africa he sent them to Virginia, Maryland, Jamaica and Barbados where he usually exchanged them for rum. He was, however, very keen that they should not linger in the New World. He gave strict orders that after delivering the slaves in America that the ship should not stay any longer than fourteen days waiting for a cargo of tobacco for the return journey.

He operated a complex network of vessels in the trade, often having several ships simultaneously in African waters. This meant he could easily exchange goods and information among his captains. In his instructions to his captains he often listed the names of the commanders of his vessels whom they might meet. He urged full cooperation between them and wrote out signals to be observed among ships in his service. For example the ship Henry in 1721-22 supplied the Sarah and the Elizabeth with goods, received 120 slaves from the Elizabeth, delivered 100 slaves to the Sarah and sold seventy-six slaves to the Portuguese before making its way to the slave market in Kingston, Jamaica.

The captains he used were experienced in buying and selling slaves. They were paid in part through a captain’s commission on slaves and goods sold and through the ability to transport slaves free of freight. They had to keep a daily account of trade. He was very concerned for his captains and their crew and when one of his ships was seized by pirates he immediately offered William Snelgrave another ship and ordered that money should be distributed among the crew.

He aimed to reduce losses of slaves by death in the Middle Passage by selling the slaves in Africa. He was concerned for the treatment of the slaves and instructed a surgeon to sail on all his slave ships, with records to be kept of deaths of slaves. Captains were also instructed to buy limes to prevent scurvy during the Middle Passage. Because of the employment of surgeons and the supply of the correct provisions Morice’s losses were usually small compared with other traders. The Judith in her voyage of 1728-29 lost thirteen of 227 slaves and on her voyage of 1730-31 she lost thirteen of 280.

Humphrey Morice was born about 1679, the only child of Humphrey Morice, citizen and mercer of London. His parents died when he was a boy and he was cared for by his uncle, Nicholas Morice and privately educated. About the year 1700 he set up business as a merchant in Nicholas Lane, London and traded extensively with Africa, North America, Holland, Russia and elsewhere.

In 1720, after the death of his first wife, Judith Sandes, who was the daughter of a prosperous London merchant and by whom he had five daughters, he moved to a house in Mincing Lane, London. In 1722 he married again, this time to Katharine who bore him two sons.

His cousin, Sir Nicholas Morice, was influential in helping him to secure a Parliamentary seat for Newport, Cornwall in 1713. He held the seat until 1722 when he was elected as MP for Grampound. He held this seat until his death in 1731. He was elected as Director of the Bank of England in 1716, served as Deputy Governor from 1725 to 1727 and as Governor from 1727 to 1729. He died suddenly in 1731, probably as a result of gout, but there are suspicions that he committed suicide.

Although he left a substantial amount of money it was not enough to pay his creditors. His debts amounted to nearly £150,000, including a claim of £29,000 from the Bank of England for bills he had discounted and which were discovered to be fictitious. It would seem that he had contributed large sums of money to the Whig cause in the hope of being given a peerage.

The collection of Humphrey Morice papers which are held at the Bank of England archive and which are published in this microfilm collection afford the researcher a wealth of detail for the history of slaving during a period when London was the focus of the slave trade.

The Slave Journals in the collection cover the period 1721 to 1730 and are all in excellent condition. They contain the orders and instructions to the captains of Morice’s slaving ships for the purchase and disposal of the slaves together with a list of goods to be exchanged for slaves. The slaves bought are listed by age and divided into Man, Woman, Boy and Girl. Prices are given for them, a man costing an average of £24 and a woman £16. (The prices are in coastal units of account and sometimes in sterling). The central role of the Europeans in exploiting and expanding the Slave Trade is well documented, as is the involvement of local Africans in the coastal trade and in bringing slaves to the coast from the interior.

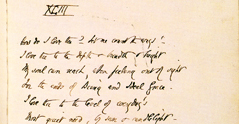

In the instructions in the journal of the Judith of September 1721 Morice tells William Clinch, the Captain exactly what sort of negroes he shoud buy:

" In the choice of your Negroes, I would have you have a regard no Negroes be under twelve years of Age nor any...above Twenty five years old and if possible buy two males to one Female...and observe that your Negroes are sound, Good and healthy and not blind, Lame or Blemished".

In the same journal is a list of the goods which were " to be disposed of in exchange for negroes". They include " Tobacco, guns, Sringe, corrall, Amber, Pipes, gunpowder, spirits and beans".

In the journal of March 1725 he tells Captain Edmund Weedon of the Anne:

" I am in hopes you will be able to purchase upwards of Two hundred Negroes, besides Gold, Elephants Teeth and Bees Wax...."

His concern for the welfare of the slaves is shown in the journal of September 1721 when he tells the Captain:

"Take care your Negroes have their Victualls in proper Season and at regular times and that their food be well boyled and prepared and do not Sufferr any of your Shipp’s Company to abuse them, always looking out and watching that they do not endeavour to rise and Surprise you which may hazard to endanger your own Life...."

Concern is also shown for the slaves in the instructions of March 1730 to Captain Jeremiah Pearce of the Judith:

"Be carefull of and kind to your Negroes and let them be well used by your Officers and Seamen...."

He is, however, keen to get as good a deal as possible from the sale of the slaves. He instructs the same Captain:

" You must be mindful to have your Negroes shaved and made Clean to look well at every Island you touch at and to strike a good Impression on the Buyers...."

There are instructions to the captains regarding the way to trade with the Africans:

" You must endeavour to hire or buy at Commenda or any other place a good large Canoe and in the Secure Canoe men to go down the Coast along with you for at Quittah and Popoe they will be of singular use to you to land and gett ashore your Goods, and carry off your Negroes, which will tend greatly towards your dispatch at those places...."

He also gives instructions to the captains on how to sell the slaves in North America and on the loading of the return cargo - not to sell only the best negroes at the first stops and to avoid long waits for return cargoes.

"You must be expeditious as Possible to take in a Loading of Sugars, for to Lye long at any of the Islands to take in a Loading, will be very detrimental to mee, And the great charge your Ship Sails at will eat up the ffreight".

The two Journals of Humphrey Morice cover the years 1708-1710. They give details of money paid and received from his business transactions with North America, Jamaica, Barbados, Africa, Brazil and Guinea in goods such as tobacco, wine, wool, sugar and silk.

His Letter Book of 1703-1706 contains business letters for those years covering trade in cloth and other commodities.

Also included are five volumes of Trading Accounts and Personal Papers, three volumes of Personal and Business Letters and one volume of Documents relating to British Trade with Africa, America and the West Indies.

The Trading Accounts and Personal Papers contain a wide variety of material.There are accounts, receipts, bills, details of wages paid to the seamen, with much on slave business. There are letters from captains giving accounts of their voyages with details of the goods traded, weather conditions, slaves bought, sold, ill and numbers of those who died on the voyage.

The following instructions from a captain to the first mate in Volume 1 give explicit instructions on how to deal with the slaves:

"Let there be great care taken in boyling their victuals well and to induce them to eat Brans let some pieces of Beefe be minced small and boyled in them..... When any slaves are taken with the small pox let them be put in the storeroom to prevent the Infection spreading and lett Mr Wilson have beefe, flower, Rice and Brandy for those Slaves whom he thinks fitting. When any Slaves die let Mr Willson with some other officer be Present at the time of committing them to the water: noting the day of the month and sickness which they died of. The slaves are to be served water three times a day, Tobacco once a week and Pipes when they want. When you see fitting give them a dram of corn brandy and more especially in a cold morning: be as saving as profitable of your London water for drinking, boyling their victualls in what you gott from the shore. Be mindful to iron your strong rugged men Slaves, but favour the young striplings or those who begin to be sick: and let them in general be washt at convenient times: in an Evening divert them with musick letting them dance".

The Personal and Business Letters cover topics such as: interest paid, the National Debt, petitions, wills, bills, inventories of goods, the sale of negroes and lists of slaves who died on voyages and the disposal of cargoes on the Coast of Africa. Included also are family papers relating to Morice’s uncle, cousin and wife.

The interesting documents relating to British Trade with Africa, America and the West Indies include petitions of planters and traders for the protection of British shipping against pirates and against Spaniards, and reasons against imposing duties on negroes imported and exported at Jamaica.

This little known collection of the Humphrey Morice Papers from the Bank of England gives researchers a fascinating resource for the study of the slave trading activities of one of the most prominent slave merchants of London during the early 1700’s. It contains a wealth of previously unstudied detail on goods traded, slaves bought and the conditions and treatment on the slave ships, revealing the important role London played in the slave trade during this period.

It offers an opportunity to examine rare historical evidence concerning the enslavement of Africans. Who were the Agents? Who kept the profits? How was the trade carried out?

|